Reviewers typically position themselves as being more or less superior to the work under review. Thus, the work being reviewed is discovered to be—discreetly or otherwise—deficient, in the light of the work that the reviewers themselves would write if only they could tear themselves away from important work—like reviewing. (Though it might be more accurate to say that they might have written if they could…) I’m afraid Rita Kothari’s Uneasy Translations: Self, Experience and Indian Literature offers no such comfort.

Archives

January 2023 . VOLUME 47, NUMBER 1In 1936, the young and upcoming Hindi writer and poet, Sachidanand Hirananda Vatsyayan, ‘Agyeya’, wrote to Banarasi Das Chaturvedi, his mentor and friend at the time, ‘It is too early yet to tell secrets especially to you’ (p. 130). A few years later, in 1944, to another friend he wrote, ‘a person like me has a very small life outside but a big inner life’ (p. 267). Throughout his lifetime, and even after, those close to Agyeya variously described him as ‘reserved’, ‘quiet’, and ‘restrained’.

This book is part of the series ‘Writers in Context’ edited by Sukrita Paul Kumar and Chandana Dutta. The time for such a series has long come and I am glad that we finally have the first books in the series in our hands. To take up Indian language writers and put together an authoritative volume on their writings in English translation with excerpts from their works and their own essays and letters, interviews with them, biographical sketches and memoirs, bibliographical details, and critical readings of their works over the years answers to the needs of scholars of Indian literature all over the world.

Although Dalit literature has had a long and variegated presence in Bengal, especially through the oral traditions of Bauls, Fakirs, Sufis and other popular sects, it remains a relatively neglected area in Dalit studies and has only recently found greater visibility via translation. Under My Dark Skin Flows a Red River, seeks to fill this gap with an anthology that combines historical and theoretical frameworks with samples of creative writing across diverse genres.

The Mendicant Prince spans multiple genres: historical fiction, real-life mystery and a legal drama that inspired a long-drawn-out pamphlet war in pre-Partition Bengal. Aruna Chakravarti breathes life into the Bhawal Sanyasi case that has fascinated generations in Bengal and Dhaka, in yet another novel that demonstrates her mastery over the genre of fiction about colonial Bengal.

Somdatta Mandal’s The Last Days of Rabindranath Tagore in Memoirs is a uniquely conceived book that provides a comprehensive look into the final months of biswakabi Rabindranath Tagore’s life when the hallowed man was ‘oscillating between fitness and illness’ (p. 164), until he passed away after a fatal surgery performed against his wishes. The book consists of translated selections from several memoirs and biographies originally written in Bengali by the poet’s associates and other well-known writers and researchers.

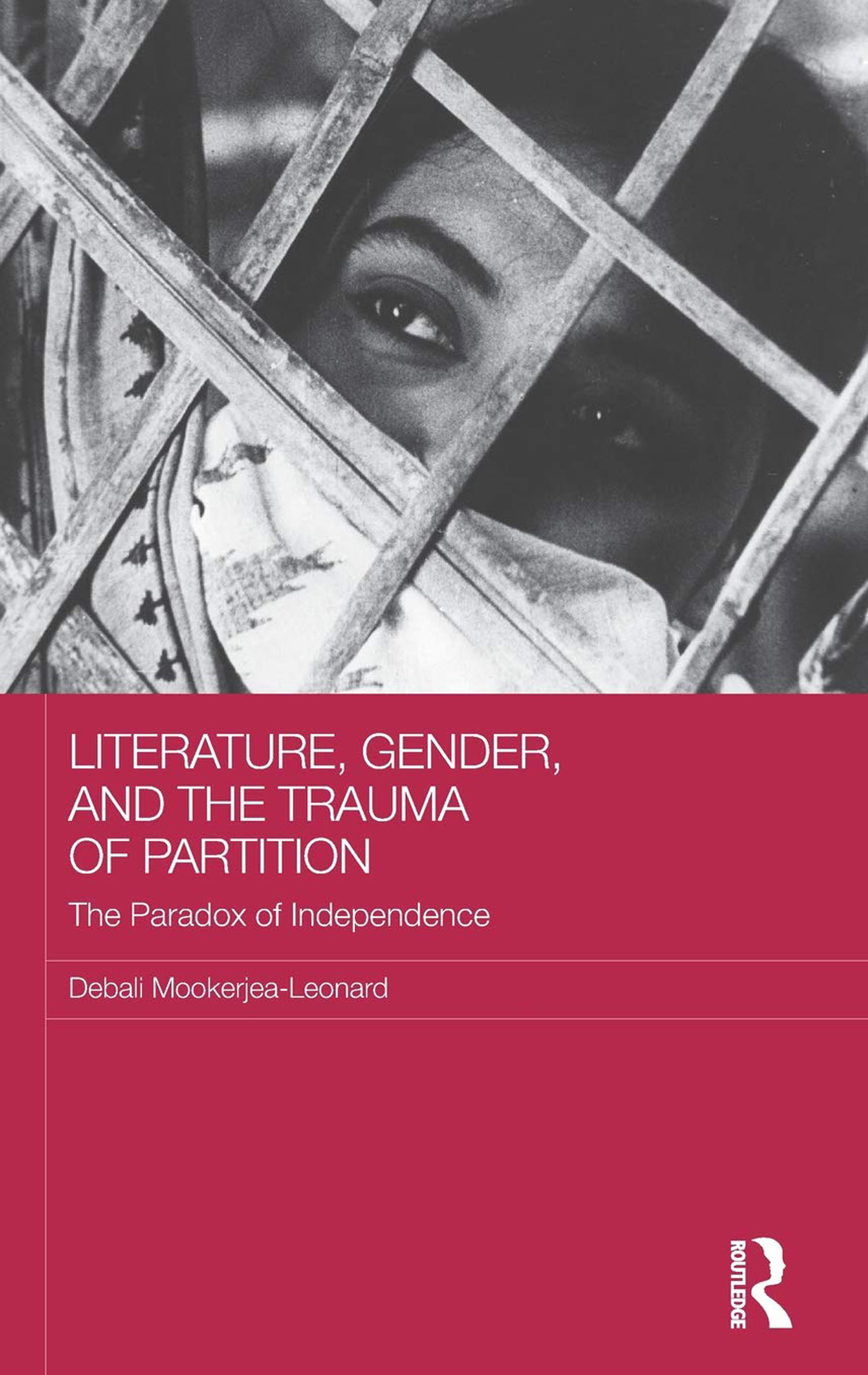

What Debali Mookerjea-Leonard achieves distinctly in this book is to effectively showcase her own reasoned angst and that of the others, regarding the lesser visibility of diverse aspects of Partition literature on the Bengal side in comparison with the abundant and a rich variety of perspectives on Partition fiction from the western side of the subcontinent. In her detailed analysis of the critical writings of such critics as Srikumar Bandopadhyay, she convincingly draws the attention of the reader to the non-acknowledgement of different Partition themes presented by several Bengali authors.

What struck me most in the Evening with a Sufi: Selected Poems by Afsar Mohammad translated by him with Shamala Gallagher are vivid, sometimes startling images such as of ‘a body like a wound peeks from your torn shirt’ or of wounds that ‘open their huge doors’ in a poem like ‘Name Calling’. Or consider the lines in ‘A Piece of Bread’ written in memory of Bismillah Khan

Although the hyperbolic title of this just minted anthology indicates a performance in the realm of extravaganza, the forty stories included within its covers do offer a dazzling spread of assured and exciting writing. In itself the anthology contains a wealth of riches; the editorial decision to print only the best writing of authors belonging to the millennial generation and Generation Z catapults this book into a budding promise: a dynamic product rather than a finished volume, which functions like a tantalizing anticipation of that which is yet to come.

When one thinks of Deepti Naval, one immediately wants to frame her into a film sequence with Farooq Sheikh, both of whom have been remarkably great actors in Indian cinema. And so, when I eagerly picked up her autobiography, A Country Called Childhood, I was half-expecting at least a chapter or two on her life as a Bollywood actress who was at the fore of ‘parallel cinema’ which has left an indelible mark in the history of Indian films.

Rijula Das’s book A Death in Shonagacchi, despite its title, is less about death and more about life and living. You cannot find a more unlikely hero than Tilu Shau, even if you determinedly looked for one. A man of unassuming looks, which is to say he is nothing to look at, short of stature with a caved-in chest, falls in love with the dark and buxom Lalee of the red-light district of Shonagachhi. To Lalee, love dove mean nothing. Can the client pay is the only pertinent question. She sees Tilu’s infatuation and ruthlessly moves to raise her rates.

Aloka Parasher Sen’s edited volume under review comprising a collection of eight essays recognizes the need to seek ‘out the “reality” of the past rather than its “truth”’ (p. 2). Inspired by Hayden White’s essay on historical fiction and historical reality, wherein White explains that ‘The real would consist of everything that can be truthfully said about its actuality plus everything that can be truthfully said about what it could possibly be.

The book is a biographical account with a difference, of an emperor, contested currently in national discourse, in a simple story-telling style to make the narrative thrilling and delightful. Written with passion and curious interest combined with theatrical melodrama and humour, it captures the multi-faceted personality of Akbar, his different moods, temperament, sentiments, emotions, compassion and open-mindedness, yet the focus primarily remains to be on the power-driven, ambitious, warrior, conqueror, imperialist, who is never free of court animosities, politics, resentments, turmoil and turbulence enmeshed in kinship and patronage.

Historian Ramachandra Guha has spoken of what he calls the ‘Boyle’s Laws’ of biography writing; named for their author, Goethe’s biographer Nicholas Boyle, they argue for a biography to be a logical progression to its conclusion, rather than the elaboration of a premise stated in advance; the drawing upon characters other than the principal to illuminate the narrative and extensive reference to sources other than those directly attributable to that subject. Winston Churchill’s views were congruent with Boyle’s on at least the first law

Peter Robb’s Ideas Matter: Debating the Impact of British Rule on India attempts in nine chapters to present a scenario on the debates regarding the impact of British rule on Indian society, economy, culture and politics. The long-debated introduction titled ‘Changing Governance, Agriculture and Identities’, highlights various colonial themes. The author starts with an analysis of the relationship between India and Britain and argues that ‘both countries would be different today’ without British rule in India.

For a long time the Partition of Bengal in 1947 and its manifold complexities and consequences failed to emerge as a subject of serious academic research, and more so in the English writing-speaking world. The reasons behind the relatively (as compared to Punjab) subdued academic attention and consequent paucity of published works on the Bengal Partition were many, ranging from ideological-political differences (among both state and non-state actors/researchers) to the ‘perception’ that the Bengali Partition experience was far less violent and traumatic as compared to Punjab.

Decentring the gender discourse has emerged as a vital task for those seeking to understand the unprecedented expansion of Hindutva politics and the social and political ground it has gained since the erstwhile Jan Sangh won just two seats in the Indian Parliament in the year 1982. To dismiss the ‘gender’ of the political formation as conservative could be superficial, pernicious or simply convenient; a closer and more incisive examination of the women of Hindutva remains the need of the hour, to use a cliché.

There is a lovely story in Navaneetha Mokkil’s Unruly Figures describing a moment from the sex worker and activist Nalini Jameela’s Autobiography of a Sex Worker. Jameela, used to doing sex work in a darkened room, is asked by her client to go into the light so he can see what she looks like. His face lights up when he sees her, and Jameela realizes for the first time that she is beautiful. Mokkil likens this to how we often ‘see’ ourselves through others.

According to the National Crimes Record Bureau data available in 2016, there is a total of 20 women’s prisons in India, housing more than 3000 inmates. Tamil Nadu has the largest number of women’s prisons, five, and they are less than half full; while West Bengal, Delhi and Maharashtra each have one women’s prison and have more than full capacity of inmates.

This book is the story of India’s monetary policy and its economic dilemmas written by a true savant and patriot who had to deal with a whole lot of crises. Dr Chakravarty Rangarajan, until his retirement in 2014, at the age of 82, devoted his entire life to serving the country in one capacity or another. He has been Deputy Governor at the Reserve Bank of India, member of the now abolished Planning Commission, then RBI Governor, the Governor of erstwhile Andhra Pradesh, and Chairman of the Prime Minister’s Economic Advisory Council. He is currently the Chairman of the Madras School of Economics.

The history of welfare provision in post-Independent India has been replete with stories of failure and leakages. Almost every public welfare programme will throw up a side story on how only a fraction of the largesse has reached the intended beneficiaries. India is known for, what Jean Dreze calls, the ‘percentage system’ under which a fixed part of the money is siphoned off as bribe by a wide range of intermediaries across the system.

Pashtuns are one of the largest ethnic groups in the world who do not have their own country but straddle across a contiguous stretch of territory, across northern Pakistan and southern Afghanistan. They have been embroiled in wars with the British, invaded by the Soviet Union and suffered an almost two-decade long interference by the United States, albeit sometimes benign.

Although the title refers to ‘Southern Asia’, this masterly survey by Ashley Tellis focuses on three countries: China, India and Pakistan. In so doing, the author differs from other western scholars and analysts writing about nuclear deterrence concerning India, who take a dichotomous view of India’s dilemma, either India versus Pakistan or India versus China. Tellis rightly takes a trichotomous view because it is impossible to consider nuclear issues in South Asia in isolation from China.

Reading the synoptic narrative of the hundred years of the chequered political career of the Shiromani Akali Dal in the volume under review makes us aware about the uniqueness of the oldest State-level Party which emanated from a religious reformist movement and went on to qualify both as a ‘regionalist’ and an ‘ethnic’ party. As ethnic Party, Akali Dal has sought and received considerable political support from the Sikhs in India and even among the Sikh diaspora, while taking up the community’s religious, social and political causes as central to the Party agenda.

The Punjab Borderland, drawing together an array of archival sources, traces the first ‘comprehensive social history’ of the Punjab border, straddling the states of India and Pakistan (p. 2). Through an extensive study of the border mobility and materiality from 1947 to 1986, it argues that the Punjab border was far more porous and accessible than generally assumed.

What happens when a state wages a war on people? How do the people navigate a system rigged against them? Flaming Forest, Wounded Valley is a result of Freny Manecksha’s decade-long experience of travelling and documenting in the two most volatile regions in India—Bastar and Kashmir. The book documents state’s action as well as inaction in these volatile regions and examines the meaning that words like ‘home’, ‘safe-space’, ‘development’ and ‘justice’ take on in a conflict zone.

Ajay Gudavarthy has through this edited volume of essays foregrounded the argument that there are internal contradictions giving rise to new power formations which are a result of conflict within and between marginalized groups. He states, ‘today, we cannot understand social dynamics exclusively as conflicts between the dominant and dominated.

2022

The significance of this book is that it adds to our understanding of Western India and more specifically the milieu of the small Parsi community in Bombay that provided the commercial, political and intellectual matrix out of which the political thought of Dadabhai Naoroji emerged. Visana suggests that in the development of Naoroji’s ideas, ‘Bombay had an especially important role to play since it was the “centre of the best political thought in India”.

Knowledge, at least in its a priori form, promises to be liberating. The basic thought of being able to learn, to question, to unlearn and then to relearn is deeply empowering. However, knowledge production and knowledge dissemination seldom remain under the control of one single individual. Knowledge can become liberating and empowering only if its systemic functioning is informed by the logic of equity, empathy and respect.

Partition is one of the major historical junctures in the history of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. When it comes to talking about the horrors of Partition, it is mainly categorized in cinema and literature. The edited volume by Nukhbah Taj Langah and Roshni Sengupta is an interesting addition to the discourse.The book does not limit itself to the horror of Partition; it goes beyond and covers its continued trauma.