Peggy Mohan, linguist and historian, argued that language is a powerful way into history and not an ‘adult’ subject. Teaching ten-year-olds about migration pushed her to rethink assumptions, from why farmers migrate to how ‘surplus males’ reshape linguistic landscapes. Children’s questions about Ashokan Prakrit or Devanagari sounds have sparked some of her deepest research. She emphasized, ‘Kids don’t want to be patronized. They can do the more difficult things that sometimes we can’t do.’

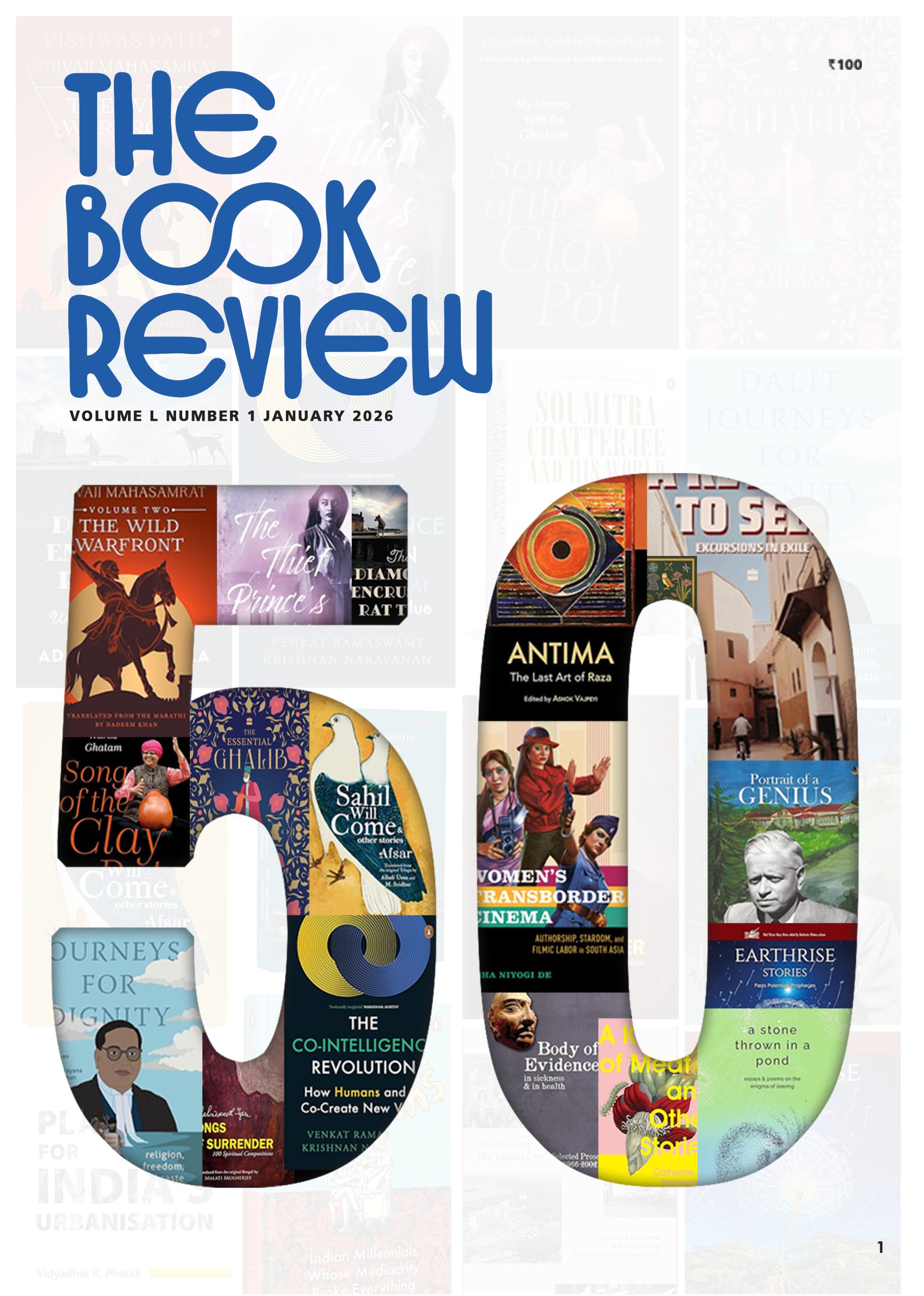

Editorial