There is a change in the manner in which cookbooks are being written now. Earlier, they were mere recipes. The transformation that has come about is that a related history about the dish, or about the concerned region, from where the recipes have been chosen are now added.

Archives

March 2018 . VOLUME 42, NUMBER 32018

Temsula Ao, a poet and a short story writer, is the recipient of several awards, among them the Padmashri and the Sahitya Akademi Award. Her works include These Hills Called Home, a collection of stories and Laburnum for My Head, her memoir, about her growing up years. And now Zubaan has brought us this refreshing novel.

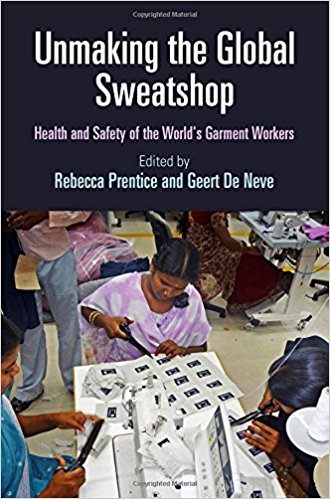

Unmaking the Global Sweatshop is a volume that brings together a rich collection of ethnographic studies which focus on the deplorable safety conditions at work and the poor status of health and well-being of workers employed within current garment production regimes.

The book under review undertakes and accomplishes the daunting task of laying bare the relationship between the capitalist class and the state in Independent India and its consequences for the specific trajectory of capital accumulation that emerged. The task is challenging as the state-capital relationship is often made invisible through laws and customs and obfuscated with the aid of faulty or irrelevant economic logic.

Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protests by Zeynep Tufekci is a brilliant account of the organization, mobilization and spread of dissent in a digital age. The over 275-page description of protests in the ‘networked public sphere’(p. 19) is a riveting account of the role of the internet in movements ranging from the Zapatista uprisings in Mexico, the Arab Spring and the Occupy movement in New York.

Ambedkar’s observation made about India almost decades ago applies equally even now to modern democratic globalized India. The unfortunate part is that over the period Ambedkar himself could not stand indifferent to the practice. Today, a diverse section of people cutting across caste, class and ideological backgrounds appreciate Ambedkar for his ideas.

2018

For half a century (from the 1920s to the 1960s), like a colossus, Master Tara Singh straddled the region, the society, the community we call Panjab. His life had immense highs and lows and his role in the

making of modern Panjab and the history of Sikh politics elicit diverse opinions.

Three bearded men, between them, occupy a major part of air time on Indian television. The first gets on TV mainly because he often generates the ‘news’ of the day and also because his face is used for hard-selling government programmes —recycled or re-invented, feasible and un-achievable, successes or failures.

Last year, when PM Modi launched the by now infamous Goods and Services Tax at an expensive event in Delhi, he was invited to the podium by an over-enthusiastic compere, who welcomed him with these words: ‘GST yaani ek rashtra, ek kar, ek bazaar, (GST as in one nation, one tax, one market) yahi hai ek bharat, shreshtha bharat (this alone is one India, great India)…

There is no doubt that Hindutva politics has established its dominance in the vast terrain of Indian politics, particularly post-2014 general elections. Its dominance is not just limited to the political victories, but the Sangh Parivar has created acceptability and respectability in different social spheres.

What counts as scientific knowledge is often a subject of popular controversies and yet science is commonly understood as being too complex for public engagement. In his book Contested Knowledge about risk controversies in Kerala, Shiju Sam Varughese contends with this particular paradox.

Tariq Thachil’s Elite Parties, Poor Voters: How Social Services Win Votes in India revolves around the empirical puzzle as to why poor people support political parties that do not promote their material interests. While this puzzle has received considerable attention in wealthy western democracies, it has been ignored in the non-western world.

Caste-based quotas, whether in education, jobs, or electoral positions, are routinely vilified for lowering the quality of the space they are applied to, because of the belief that those chosen through quotas are inherently inferior to those selected on open, or non-quota, positions. This widespread belief transcends the boundaries between academic arguments and popular perceptions.

Purulia is a town in Bengal’s western periphery. Under British rule, it was the headquarters of the sprawling Manbhum district. At Independence, the entire district was allocated to Bihar. But its substantial Bengali population actively resisted what they perceived to be Hindi imposition. Demonstrations soon became a daily occur-rence as the State administration strove to contain the language agitation.

The recently concluded Assembly elections in Himachal Pradesh had a very interesting moment when a 101 years old voter pushed the button at his polling booth in the remote Kalpa village in Kinnaur district of the State. Shyam Saran Negi, would have been passed on for any aware and conscious senior citizen who believes in exercising his duty of citizenship by voting, had he not been India’s first voter.

Arecent revival in the unearthing culinary histories of India has brought forth some marvellous writing. The study of food has been serious business in certain parts of the world for quite some time, with university departments dedicated to the subject. However, India has lagged behind in this respect. This gap is slowly being filled, both through academic and popular writing.

Making tea is an art and making a perfect cup—hold on, is there a universally accepted way of brewing tea? There is, if we believe, the International Standard Organization; but who cares! George Orwell liked it without sugar, Maulana Azad liked it without milk —he thought adding milk is a British innovation. Hamid Dabashi likes it only in transparent cups. Gandhi didn’t like it all. Kashmiris prefer it with salt and Tibetans like it with Yak butter.

This masterly new work by Delhi University historian Anshu Malhotra enlivens the study of religion, gender, and caste in late colonial Punjab, with compelling explorations of post-Partition religious and cultural forms. The centre of her study is Piro (d. 1872), a female devotee of a nineteenth century guru named Gulabdas (1809-1873), who led a sect that came to be known by his name: the Gulabdasis.

Muslim life in urban India has attracted fresh attention since the publication of the Sachar Report a good decade ago. The subsequent debate has gone through three distinct stages. Initial scholarship, including the report itself, outlined and quantified the extent of Muslim disadvantage with a broad brush.

Akhil Katyal deals with a subject that has been researched upon recently. Bringing socio-psychological identi-ties and religious identities together in the same research needs courage, especially in the contemporary political ambience in the country. The blurb hints at certain exciting debates, Katyal unveils much more than that.

Performance and the Political uses five critical modes—vision, voice, ges-tural, machinic and animality to address questions that are intimately linked to our present such as: what is the political? How do we engage with performative practices in which transgression is not mapped through the paradigms of agency and individualized resistance? Spanning the time period from Emergency to neoliberalism…

The historian Ronald Hutton, an acknowledged expert in British folk-lore, and pre-Christian religions and paganism in Early Modern Britain, author of The Triumph of the Moon: A History of Modern Pagan Witchcraft (1999) and The Druids: A History (2007), offers yet another treat to his readers.

Honour as the bedrock of family life and values is a familiar and well-researched idea in the literature on gender, family and kinship in South Asia. Honour Unmasked, while locating itself within this terrain makes a significant contribution to the field for the following three reasons. First, it is valuable for the site and context of study, as ethnographic work on gender and power in Pakistani society is relatively limited.

Enclosures and boundaries have a conflicted meaning for women. Enclosures are often not safe spaces for them and women have to constantly resist boundaries in order to live their lives. The book under review looks at how ‘conventional Tamil symbols—unbroken enclosures like bangles, pots, wedding halls, the kolam or doorstep design—signifying auspiciousness’ (p. 104), are reinterpreted in the songs of Tamil Paraiyar women as signs of deprivation and restriction.