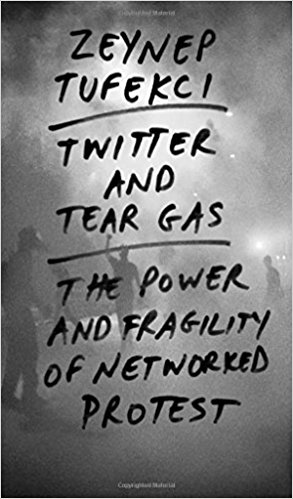

Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protests by Zeynep Tufekci is a brilliant account of the organization, mobilization and spread of dissent in a digital age. The over 275-page description of protests in the ‘networked public sphere’(p. 19) is a riveting account of the role of the internet in movements ranging from the Zapatista uprisings in Mexico, the Arab Spring and the Occupy movement in New York. ‘Thick descriptions’ of protests and ethnographic details of informal communities of friends and connected protestors from varied locations: Gezi Park in Turkey, Tahrir Square in Egypt and New York’s Zuccotti Park create a narrative which presents a convincing argument about the power of the internet, especially, the social media and their ability to inspire, organize, share, disseminate and archive protests calls, messages and videos which governments find increasingly difficult to control in the transnational world of the web.

Tufekci springs no surprise when she argues that leaderless revolutions find success as they reach out to people through Twitter mentions and pings. However, the strength of her propositions lies in their substantia-tion. Participant observations and conversa-tions with employees from Facebook, like with Richard Allan on the ban of Kurdish content by the social media giant add layers of meaning to the text—the logic behind Facebook’s design of its algorithms and the fact that users were unaware that an algorithm was determining what they saw or read. It this approach and methodology that distinguishes Twitter and Tear Gas from somewhat similar arguments made by her predecessors, like the much acclaimed Transnational Protest and Global Activism: People, Passions and Power edited by Donatella della Porta and Sidney Tarrow (2005). In her conversational and easy-to-follow style, Tufekci introduces key concepts of digitally mediated communication with alacrity adding a scholarly dimension to her work. She applies these concepts to the narrative to study how they impact the success or failure of social movements. For example, in her insightful description of what she calls ‘an algorithmic spiral of silence’ attributable to the opaque, proprietary and personalized nature of algorithmic control on the web, she enunciates how it is difficult for activists to ascertain what drives visibility on the web. Therefore, they can never figure out whether it is their cause that is not finding traction with the public or the algorithmic filtering that is suppressing the story. This ‘algorithmic governance’ (p.162) is the ‘new overlord that social movements must grapple with’, the author sums up.