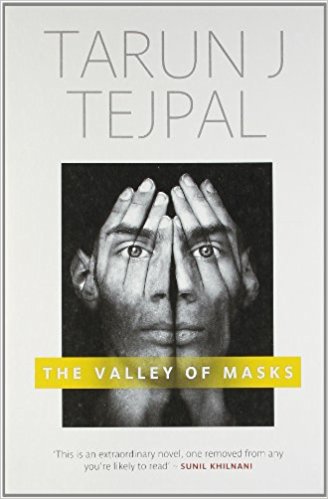

Tarun J. Tejpal is the founder-editor of Tehelka, well known for its investigative reporting; over the years, he has exposed various scams and malpractices in India. The Valley of Masks, his third novel, is very different from his earlier novels which were in the realistic mode. In his first novel, The Alchemy of Desire (2005), the hero is a journalist who is writing a novel; he is passionately in love with his wife, and the book contains many erotic passages. He drifts away from his wife when he gets involved in the journals of an American adventuress they discover in an old house. Tejpal’s second novel, The Story of My Assassins (2009), also has an unnamed journalist as protagonist. The police tell him that they have discovered a plot to assassinate him, and arrest five suspects. His mistress Sara believes that the suspects are victims of the state machinery being manipulated by selfish politicians. All the characters—the protagonist, Sara, the police officer, and the five suspects, are memorable. The novelist presents an inside view of Delhi, exposing the nexus between politics, industry and money, based on his own experiences as a journalist. The Valley of Masks is not set in any named city. It presents a terrifying dystopia, born of the human search for perfection.

January 2013, volume 1, No 1