Most people tend to view autobiographies ambivalently partly because there is something narcissistic about them and partly because you do wonder, from time to time, if you are really interested in all the details of someone else’s life. Also, the best autobiographies are usually insensitive to the people who figure in them and the worst ones are a dead bore because they hold back so much. Problem is, it is only after purchasing them that a reader finds out.

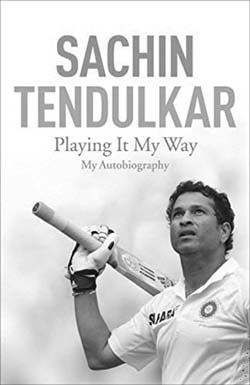

The two autobiographies under review here fulfil the criteria, one each. Sachin Tendulkar has written a disappointingly flat account of his life. Naseeruddin Shah, on the other hand, has written a very racy account of his life. No holds are barred, although you do get the sense occasionally that he is trying his best not to go the whole nine yards.

February 2015, volume 39, No 2