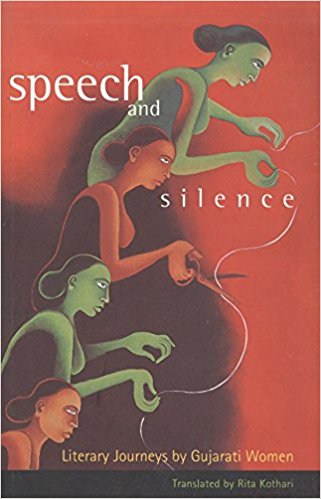

There are occasions when you feel a kind of bliss when you read a book that is able to deal with things that are dear to your heart. Here is such a publication: an anthology that collects writing by Gujarati women over a century. Rita Kothari has done an excellent job of selecting and translating texts that speak not only about the usual constraints that these women live in, but also the subtle and serious gaps of silence that speak more of the ‘truths’ about life. It takes some time to realize that silence most probably is the most articulate forms of speech – it leaves the options of interpretation open to the listener. Silences speak more than all the cacophony of words in a system where women remain under the control of men, of social norms and certainly, also of conventions. The book contains eighteen stories; beginning with ‘Entries from Vanamala’s Diary: An Account of A Tragic Decline’ by Leelavati Munshi writing in the early twentieth century, to ‘The Transience of Things’ by Vinodini Neelkanth writing towards the end of the century.

It covers a wide range of texts, of various kinds of writing trying to make sense of the reality they lived in. There is an excellent ‘Introduction’ to the book written by Rita Kothari and it would be worthwhile to start the discussion from here.

She says that: “More than another industrial sector, the popular culture industry relies on online communities to publicize and supply testimonials for their merchandise.” The strength of the online neighborhood’s power is displayed by means of the season 3 premiere of BBC’s Sherlock. Energy customers – These individuals push for brand spanking new discussion, provide constructive suggestions to group managers, and generally even act as community managers themselves. Enforces guidelines, encourages social norms, assists new members, and spreads consciousness in regards to the group. On the whole, virtual community participation is influenced by how individuals view themselves in society in addition to by norms, each of society and of the web community. Amy Jo Kim has categorised the rituals and stages of on-line neighborhood interplay and called it the “membership life cycle”. There are two main kinds of participation in online communities: public participation and non-public participation, also known as lurking. Meta Platforms, the proprietor of Facebook, additionally owns three other main platforms for online communities: Instagram, WhatsApp, and Facebook Messenger. Boards observe a hierarchical structure of categories, with many in style forum software platforms categorising forums relying on their goal, and permitting forum administrators to create subforums inside their platform. Most high-ranked social networks originate in the United States, however European companies like VK, Japanese platform LINE, or Chinese language social networks WeChat, QQ or video-sharing app Douyin (internationally generally known as TikTok) have additionally garnered attraction of their respective regions.

Social networks are platforms permitting users to arrange their very own profile and construct connections with like minded people who pursue related interests by means of interplay. Blogs are amongst the major platforms on which online communities type. It has been argued that the technical points of online communities, such as whether or not pages could be created and edited by the general user base (as is the case with wikis) or solely sure customers (as is the case with most blogs), can place online communities into stylistic categories. Each lurkers and is chnlove.com legit posters ceaselessly enter communities to seek out answers and to gather general data. Companies have additionally began utilizing on-line communities to communicate with their clients about their products and services in addition to to share information concerning the enterprise. Online communities have additionally pressured retail corporations to change their business methods. It has even been proved helpful to treat on-line commercial relationships more as friendships slightly than business transactions.

Sixty nine This private connection the consumer feels translates to how they need to ascertain relationships online. When you’re single, your smug associates in relationships will inevitably try to offer their help, by repeating statements like: “you’ll discover someone when you least count on it†and “patience is a virtueâ€. When you’re writing your profile, make sure that you’re providing your readers with trustworthy information about who you are and what you’re looking for in a relationship. “Apps are great, and they’re additionally the only method you’re going to fulfill folks right now. With time extra advanced options have been added into forums; the flexibility to attach recordsdata, embed YouTube movies, and send personal messages is now commonplace. For example, it is very important know the security, entry, and expertise necessities of a given kind of community as it might evolve from an open to a non-public and regulated discussion board. Lurkers are individuals who be a part of a virtual neighborhood however don’t contribute. Participants additionally join online communities for friendship and help.

Many online communities referring to well being care assist inform, advise, and support patients and their households. You must also take care to truthfully mirror who you’re on your teenage relationship profile. On-line dating is probably the best option to get over an ex. As of 2014, the biggest forum Gaia On-line contained over 2 billion posts. Moderator: Moderators are sometimes tasked with the each day administration tasks resembling answering person queries, coping with rule-breaking posts, and the moving, enhancing or deletion of topics or posts. Administrator: Directors deal with the forum strategy including the implementation of latest options alongside more technical tasks similar to server upkeep. This leads to changes in an organization’s communications with their manufacturers including the data shared and made accessible for further productivity and earnings. Blogging practices include microblogging, where the quantity of information in a single factor is smaller, and liveblogging, in which an ongoing event is blogged about in real time. Be authentically you when it comes to crafting the prompts and data in your profile, said Quinn. And some methods you are able to do that is by mentioning errors in her profile, like spelling errors or highlighting issues in the background of her pics.