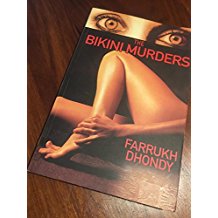

‘Who is Johnson Thhat? And how has he managed to escape justice for so long, even when in jail?’ reads the intriguing blurb on the back of Farrukh Dhondy’s The Bikini Murders. The title itself hints at a potent combination of sex and violence, reinforced by a lurid picture of bare honey-hued legs and a pair of staring brown eyes. All designed to lure the unsuspecting reader just as the protagonist of the story did with innocent tourists. Despite author Dhondy’s denials in the popular media, The Bikini Murders seems to be ‘loosely’ based on the life of the notorious killer Charles Sobhraj. The resemblances are too uncannily similar to be entirely coincidental. Sobhraj has met Dhondy several times, ostensibly to secure the services of a literary agent for his memoirs. Sobhraj has threatened to sue Dhondy for basing the book on his life story, a fact which can only help to boost book sales and garner welcome publicity for the author. Those who have followed the life and times of Charles Sobhraj can indulge in a game of ‘Spot The Difference’ with the incidents depicted in the book.

On the face of it, The Bikini Murders is the story of Johnson Thhat, a half Vietnamese-half Indian con man, killer and arms dealer with a French passport and a long line of girl friends—just like Sobhraj. Born Govind Jaisinghani to Janimal, ‘John’ Jaisinghani, a diamond merchant of dubious origins and a Vietnamese bar girl in Saigon, he was called John’s son. The surname arises out of a curious mistake by a Vietnamese immigration assistant, who, when asked to ‘write that down as his surname’ actually wrote the surname as Thhat. This is one of the few original parts of Thhat’s story that probably does not resemble Sobhraj’s tale.

The young Johnson moves with his mother and French stepfather to France. His mind rebels against the contradictions of his Catholic education rejecting Moses’s Commandments in favour of his own brand of morality: ‘Wrong is profitable, right is not. There is no God, there is only the police.’ Dhondy attempts to trace the beginning of Thhat’s amoral life to his moral education, or rather the lack of it. We are still unconvinced as to why the fifteen year-old Thhat takes to a life of petty crime in the Parisian suburbs. Was it just to show who is in control? He claims not to have had a troubled childhood, nor did he want the money.