This book, on one of the most formidable musical talents of this century, shatters one’s reverie. Those of us who live, breathe, and draw our sustenance from Hindi film music (HFM), would prefer to be enveloped by its versatility, complexity and the sheer richness of its musical variety, and not have to think about the behind-the-scenes machinations, the power play, personal rivalries, technological changes, and most importantly, the shifting idiom of film making itself, inevitable with the passage of time—in other words, the whole external context—that produces the music we so enjoy.

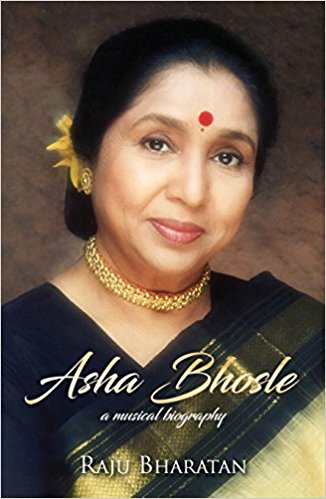

Raju Bharatan, the well-known music commentator, opens several well-guarded doors, and allows us a peek into all of these factors, which not only shaped the career of the subject of his book, Asha Bhosle, but indeed, of the entire film music industry. The result is a gripping, fascinating account, though not necessarily a pleasant one, which reveals the human frailties of several of our musical heroes, and exposes their dark side, warts and all. Bharatan, as an insider, is uniquely qualified to write this account, given his special ringside position, and his close personal equations with everyone that he writes about, which made him privy to several private stories. However, the book is not only about personal relationships which have been the subject of much gossip and speculation in the media. The value addition of the book comes from its discussion of the world of studio recordings, the making of musical monopolies and the concomitant cut-throat competition that were as vital a part of the making of specific musical trajectories, as innate talent or abilities of singers.