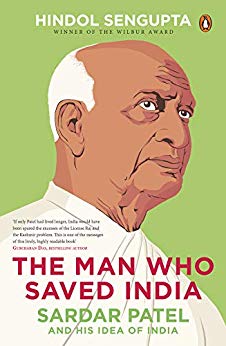

In The Man Who Saved India Hindol Sengupta brings together the political history of early twentieth century India, and biographical details of Sardar Vallabhbhai Jhaverbhai Patel’s life to show the integral role of political icons in the functioning of the social, economic, and political life of the newly formed nation-state of India. The display of political icons through the construction of statues, naming of roads, or of celebration of specific dates is more than ritualistic remembering. These acts are ways of establishing legitimacy of the new state, and of implanting new values and beliefs. The creation of compelling visual symbols was a key aspect of the new India to capture public enthusiasm, inculcate novel ideas about statehood, and implant loyalty in the minds of the citizens of newly formed India. In this persuasive construction of the visual representation, Sengupta argues, Gandhi and Nehru emerge as distinctive figures. Patel, however, gets erased from public histories.

Without falling into the narrow traps of the Left-versus-Right wrangle, Sengupta quotes Rajmohan Gandhi: ‘The establishment of independent India derived legitimacy and power, broadly speaking, from the exertions of three men, Gandhi, Nehru and Patel. But while its acknowledgements are fulsome in the case of Nehru and dutiful in the case of Gandhi, they are niggardly in the case of Patel.’ Throughout the text, Sengupta attempts to retrieve the story of Patel who was a pragmatist and could secure the integration of the Princely States into India, but not the filial affection of Gandhi because of his non-eloquent nature. But even this aspect of Patel’s life is not told with a foreboding sense of gloom. Sengupta presents a Patel who willingly let his elder brother Vithalbhai Patel to take his chance to study law in England in the same way Patel let Nehru serve as the President of the Congress for three terms. Patel in Kheda Satyagraha, later in Bardoli, and finally in his disagreements with Subhash Chandra Bose or BR Ambedkar, as Sengupta puts it, appears as an ‘Instinctive Nationalist’, whose ‘sense of self and freedom needed no theories by what we call as Dead White Males, it came straight from a connection with the soil, the earth that he had seen his father till.’ This was a politician who let go of accolades for his personal sacrifices, but who refuses to accommodate any changes to the integration of Hyderabad. In Sengupta’s narrative, Patel is a statesman who negotiates, threatens, and bargains to create what we know as India today.