Sachin Dev Burman was a colossus, and the book under review is a fitting tribute to him. Though Hindi film music started in 1931 with Alam Ara, by the time SD Burman started composing, it was still finding its feet. So, it is not surprising to find that he might have been the pioneer in setting the trend of getting lyrics being written to tunes. It all started with the song Dol rahi hai naiya from Shikari (1946), because SD Burman was yet to come to grips with Hindi/Urdu.

An early lesson learnt by Sachin was to compose tunes which the man on the street appreciates. He learnt it the hard way as tune after tune composed by him was rejected by the head of Filmistan studio S Mukherji. He was about to give up when he heard his tune being hummed by a boy who used to run errands for them. That tune was selected, and a precious lesson learnt. Earlier the same boy used to hum Naushad’s tunes.

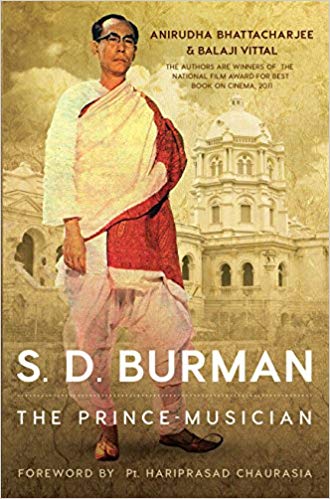

The prince of Tripura, who traded his princedom for music kept on evolving with the times and adapting to the changing tastes, while remaining true to his core musical influences—Bengali folk and Indian classical. His formula for success was keeping tunes simple with minimal orchestration, so that the tune and the singing voice shone through. Himself a nonpareil singer, he drew out the best from Rafi, Lata, Kishore, Asha, Hemant and Geeta.

What distinguished Burman from the other composers was his cinematic sensibility. The incident about Jaanu jaanu re from Insaan Jaag Utha is telling, where he enquired about the distance between two vehicles where the song was to be picturized and then walked between that distance to calculate at which intervals to put clinking of bells.

Here songs are analysed threadbare. Read this excerpt on Khoya khoya chaand: ‘The song was structured on the notes—not the progression—of raga Dhani, and followed an interesting arrangement pattern. It had four interludes and all were different. The first used the flute/piccolo and guitar; the second was mostly built on the mandolin and accordion; the third interlude had only Rafi’s voice bridging the stanzas; and the final one started with a E-seventh chord strummed on the guitar which was also used as the prelude, followed swiftly by the violin, mandolin and the flute.’