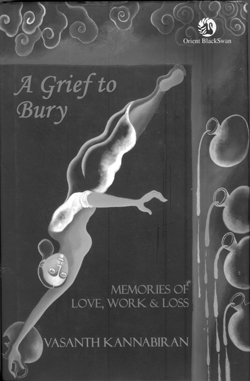

A Grief to Bury: Memories of Love, Work and Loss is a series of conversations with twelve Indian women who reflect upon the internal dynamics of their long enduring relationship with their spouses. They also share their individual coping strategies at the traumatic loss of their loved one, either suddenly or after a prolonged illness. Vasanth Kannabiran’s subjects have an established identity in the public sphere—be it social activism, academics, the fine arts or literature. As Kannabiran suggests, these women who were born before Independence and come from a common class background, share ‘a commonality of values’ derived from the nationalist period. Their life-narratives indicate a socialist orientation, as well as strong feminist ethics.

August 2013, volume 37, No 8

Wow, fantastic blog layout! How lengthy have you been blogging

for? you made blogging look easy. The whole glance of your web site is great, as well as the

content! You can see similar here ecommerce