There’s a certain kind of writer who should be allowed to grow old only if he promises to do it disgracefully. Many of Hanif Kureishi’s fans would argue that he belongs to this group, and perhaps some of the disappointment that a faithful Kureishi reader feels when reading Something To Tell You stems from the fact that this is such a neatly wrapped, conventional, sedate novel.

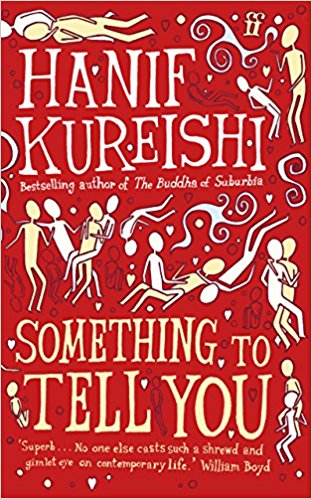

Something To Tell You could be seen as the bookend to Kureishi’s Buddha of Suburbia. It features a similar laundry list of characters, ranging from the eccentric to the forceful to the lost, drifting through the landscape of Britain’s suburbia. Many of Kureishi’s characters are either deeply seductive or determinedly mundane, caught in political causes or domestic dramas that are large enough to encompass and engulf their lives. In this novel, Kureishi’s sixth, he stirs so much into the mix that what emerges is a thick soup where no particular ingredient stands out.

The central character is Jamal Khan, psychoanalyst: ‘Like a car mechanic on his back, I work with the underneath or understory: fantasies, wishes, lies, dreams, nightmares—the world beneath the world, the true words beneath the false… At the deepest level people are madder than they want to believe.’ It’s promising stuff, but the story unfolds in predictable ways. Jamal has his own secret, one so dark that when he unburdened himself to his own analyst, the experience was classically cathartic, unleashing floods of shit and vomit in the aftermath of the session. As Jamal, now middle-aged, looks back to the world of 1970s suburbia, where his personal tragedy is set, Something To Tell You flashes into beguiling life every so often. Jamal may be the quintessential dull character made interesting by circumstance, but many of the people who surround him are fascinating — Kureishi has a master’s eye for speech, dialogue and the quirks of the individual, and there’s much to hold the reader’s attention. There’s Jamal’s tattooed-and-pierced sister Miriam, a cameo appearance by Karim from The Buddha of Suburbia, and another by Omar Ali, now ‘Lord’ Ali, from My Beautiful Laundrette. Karim discusses the negatives of being on Celebrity; Ali is now one of the smooth millionaires who mushroomed in Tony Blair’s warmth. Jamal’s London is as detailed as ever, from the unlimited menu of sexual possibilities to the children’s school that comes recommended by Mick Jagger.

It’s when Kureishi drags his attention back to the plot that Something To Tell You sags. Jamal’s most important love was with an Indian girl, Ajita, who carries her own set of secrets — secrets rendered almost banal in the retrospective gaze of the therapist who has, almost literally, heard it all. But as a young man, what he learns sparks a tragedy; he and his friends confront Ajita’s father. In the misadventure that follows, the man dies, leaving Jamal and his friends marked in very different ways. In the aftermath of this death, which is laid securely at the doors of those who had organized protests against Ajita’s father’s factory, Jamal introduces a compelling interlude in Pakistan. He and his sister Miriam are reunited with a father who smells almost comfortingly of alcohol, and to the world of Karachi. Neither Karachi nor Pakistan are what he had imagined; instead of the spirituality Miriam expects to find in Karachi, she and Jamal discover a ruthlessly materialistic place: ‘Deprivation was the spur’. His father is a trapped man, rare in Karachi for his integrity, but yearning not for Britain so much as for Bombay. There’s a moment of genuine poignancy here; Jamal is at home in Britain in a way his father will never be in his own country.

But that moment passes as Kureishi returns us to the world of the couch and the closet, and introduces a new but ineffectual plot twist. As one of his friends attempts to shoulder his way back into Jamal’s life, the now-respectable therapist has to decide what to do with this particular twist in the narrative. He is at peace with the past; the moment when the man he has inadvertently murdered ‘clung to me, his fingernails in my flesh’ has passed. What he has to solve now is his friend’s demand for redemption and reparation; the incident damaged his friend far more than it damaged him, and for a brief moment, the secure foundations of his comfortable therapist’s life are rocked. But only briefly; Kureishi is unwilling to take this book into the messy, action-packed territory of the conventional thriller, and the threat peters out, leaving a kind of resolution in its wake.

Kureishi’s preoccupation is with the stories we can and can’t tell, with the narratives we suppress that may come back to haunt us, and yet as Something To Tell You limps to a desultory close, it resembles nothing more than a rambling session on the psychiatrist’s couch. The vast and often amusing, sometimes tedious landscape of this novel is littered with the jargon of psychiatry — avoidance, catharsis, subliminal memories, the ‘spume and irruption’ of the unconscious — but few of the profession’s deeper insights. There are moments of illumination, as when Jamal remarks that ‘Listening is not only a kind of love, it is love’ But as with many of the key insights and observations in this novel, it’s left to lie there on the couch, never coming to life. Kureishi might argue that this is the right shape for a novel of this decade, that indeed, the novel should be loosely constructed of random conversations, that it should introduce you to people who flit in and out of the narrative just as real people do in our lives, that it should be full of incident and trivia simultaneously, that it should avoid closure, since most people’s lives have little closure in them. For the reader, though, Something To Tell You doesn’t have nearly enough to say.

Nilanjana Roy S. Roy, a critic, is currently the editor of Tranquetor Publications (East-West Books), New Delhi.