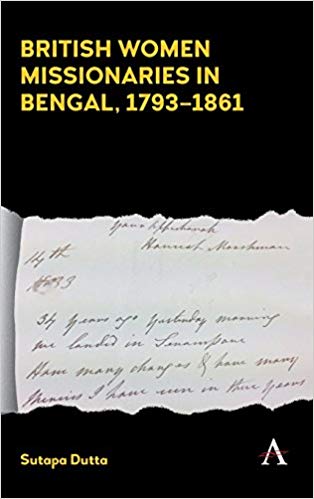

While William Carey’s name is etched in the history of missionary activity in India, arguably little is known about Hannah Marshman, who worked alongside her missionary husband, Joshua Marshman, as well as Carey. Similarly, Mary Ann Cooke, the first ‘unmarried’ woman sent to do missionary work in India, has had few biographers. Women partook in significant ways in the missionary enterprise and the monograph under review seeks to retrieve the voices and experience of such ‘exemplary women’ (p. 3) in nineteenth century Bengal.

This story of feminization of the missionary endeavour is actually told in only four chapters, the first two chapters setting the context for British colonial and missionary presence in Bengal. By the 1820s, British popular opinion supported an active outreach amongst ‘native’ women and by the 1840s, a trickle of ‘single lady missionaries’ arrived in India. In the final two chapters, readers are introduced to the life and work of Hannah Catherine Mullens (1826-1861) remembered as the ‘Apostle of the Zenana’. Mullens grew up in a missionary household, spoke fluent Bengali, was married to a fellow missionary, began sustained visits into native homes and is popularly credited with writing what is considered to be the first novel in Bengali, Phulmani O Karunar Bibaran (The History of Phulmani and Karuna) in 1852. By 1860s, when the book concludes, citing the death of Mullens as indicative of the end of first phase of missionary activity in India, missionary presence had grown manifold times. Following the Wood’s Despatch of 1854, missionaries were especially welcomed in the educational sphere to fill the void in native education, and this development, among others also expedited missionary women’s entry into India.

And as is well known, women outnumbered men across various missionary denominations by the early twentieth century. However, women were present in the earliest of missionary endeavours in India. Carey had insisted that only married men, accompanied by their wives and prepared to lead a frugal life, venture into ‘heathen’ lands. Apart from acting as companions and ‘helpmeets’, women were a guarantee against men deserting the task of spreading the gospel and marrying local women as some of them had done in faraway Tahiti, seriously jeopardizing the whole mission in 1796. The model of the ‘good’ mission wife emerged from new faith in evangelical beliefs and practices, and apart from being the ‘stabilizer’ and ‘conscience keeper’, she was expected to run schools and boarding houses, while also reproducing the western Christian family, presenting a clearly ‘utilitarian’ rather than ‘decorative’ model of femininity. However, this idyllic arrangement was often shattered by the harsh climate, penury, disease and death in the colonies. Carey’s own wife was reluctant to accompany him initially, and while in India lost her sanity following the death of her five-year old son and eventually passed away in confinement. Carey was widowed twice and ostensibly craved domestic bliss all his life.