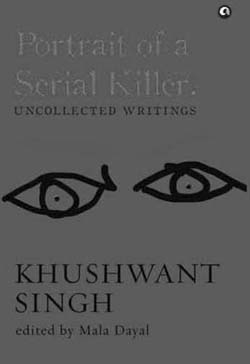

Having been close to Khushwant and hearing countless stories firsthand, reading the book made me feel as though I am sitting by him, listening to him recount his impression of ideas, people and places. He remains the best raconteur I knew, and will probably never meet anyone better.

October 2015, volume 39, No 10