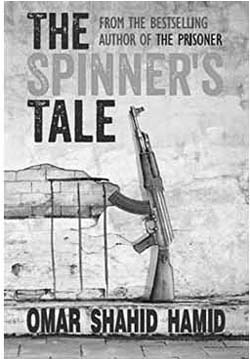

The Spinner’s Tale is a confusing title for this book. The Making of a Jehadi would have been a more apt title for it. It begins with an improbable scene. A master terrorist who has tried—twice—to kill the president of Pakistan is transferred by the police to a hole in a desert, that too near the Indian border (instead of being locked up in Kot Lakhpat jail, or any other maximum security prison, or shot-while-he-wastrying-to-escape on the way to one.) What is more, he is left there, in the hole in the desert near the Indian border, in charge of a bunch of rural policemen who have never before seen a jehadi, let alone kept watch over one.

October 2015, volume 39, No 10