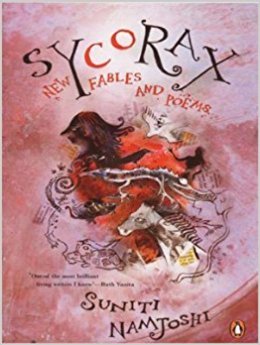

For a hedonistic reader who reads purely for pleasure, it is galling to constantly be told what to look for in a book—that its worldview is coloured by certain political views or a childhood trauma or an agenda. Or that so and so’s writing is today’s fashionable flavour, magic realism, so you criticize it at your peril. Worse still is it to have your favourite writers—long since gone and taken their wages, bless them—labelled racist, sexist, imperialist or what have you. It’s no use protesting. Meaning is fascist, aver the deconstructionists and we have perforce to accept that what we see is what we are intended to see; that underneath that charming façade lie all kinds of hitherto undreamt of horrors. Which explains the delicious sense of satisfaction, of having turned the tables on your tormentors, when you escape the critics and come afresh to a feted writer like Suniti Namjoshi, well-known feminist writer, to find a whole delightful new world. Not being very fond of the genre, I had read none of her previous books nor any reviews of them when I began Sycorax: New Fables and Poems. Expecting gloom, doom and heavy-handed isms, it came as a great surprise to find something so light, airy and refreshing—a very soufflé of a book. This is not to accuse it of being insubstantial, for the issues it addresses are serious ones—old age, death, love, identity, motherhood, child abuse… Yet, these are approached obliquely, making them more bearable (for as T.S. Eliot said, mankind cannot bear very much reality); a lightness of touch, a playfulness and an acceptance of what is. Farfetched as it may seem, these qualities seem to echo the underlying worldview of well-loved childhood classics like The Wind in the Willows. For instance, take the fable ‘Entente Cordiale’, in which Suniti is Suniti, who has failed to live up to her Sanskrit name, and River, equally inappropriately named, is a kelpie—whether the Australian dog or the mythical creature is unclear and immaterial. The camaraderie between them as they sit side by side staring at the waters of the muddy Yarra emerges as more important than the issues that they are arguing: ‘After all, it was pleasant by the riverbank.’

July 2007, volume 31, No 7