“From the mundane to the marked, everything goes through a scanner in the head from the viewpoint of being a Muslim. And living the Muslim tag. You cannot run from it. You cannot hide from it. You cannot embrace it.” (p. 68)

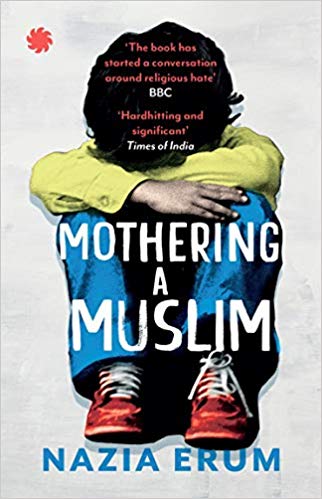

The author, Nazia Erum, runs a fashion start up. She is an educated, working woman, living in a metropolitan city. Erum became more aware of her identity as a Muslim around the same time that she realized that her daughter will grow up as a Muslim. These ideas are germane in a world that she describes as ‘increasingly polarised’. It is in this context that she felt the need to document the experiences of young children at school, in the specific context of the religious identity assigned to them.

All the children and families interviewed and documented in the book are from Muslim background and mostly from middle and upper middle class contexts, living in urban India. This highlights a key point that Erum has repeatedly, albeit subtly, brought to the forefront in the book: class and educational background do not deter discriminatory behaviour.

She writes, ‘Hate affects not just the tormented but also the tormentor’ (p. xvi). It resonates with Freirean notion of oppression. It is not just the oppressor but also the oppressed that are at a loss. Much as the ones who are discriminated against tend to suffer, those who discriminate against minorities are also living in a world that does not accommodate, much less celebrate diversity. While this is applicable to discrimination against Muslims across the world, Erum also points out to the kind of discriminatory stance that Muslims tend to take against each other on the basis of what they consider is an authentically Muslim life.