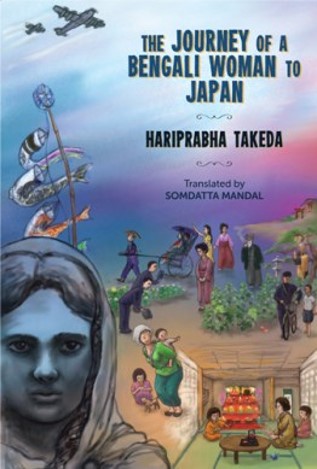

She is by no means an adventurous traveller recounting her excursions into ‘the Land of the Rising Sun’ wrapped in the secrecy of its isolation from the rest of the world. She was following her Japanese husband Oemon Takeda to visit her Japanese in-laws living in a small village near the town of Nagoya. Hariprabha Takeda’s observations are brief, but sharp, describing her everyday life as a stranger admitted into a hitherto hermetically sealed culture.

As Kazuhiro Watanabe explains in the numerous Apendices that add to our understanding of Hariprabha’s life and writing, ‘The year 1912 in which Hariprabha Takeda and her husband came to Japan was a monumental one in Japanese history. That same year Emperor Matsuhito died in the month of July, ending the forty-five year long Meiji era. The period under Matsuhito’s regime is known as the Meiji era, and during that period Japan did away with the traditional military rule that had endured for centuries, and started her march towards modernity’ (p. 187). For Oemon Takeda these steps would take him to the Bubbles Soap Factory in Dhaka as a technician. His experience would enable him to eventually start his own soap factory. He is credited with having introduced the use of glycerin in the manufacture of soap at his Dhaka Soap factory. One of his brothers, Toshan Takeda also joined him. We hear all these details, not from Hariprabha but from the entries made by some of her relatives and scholars at the end. We are also given to understand that what may have brought the couple together was the growing influence of the Brahmo Samaj movement of the early 1900s.