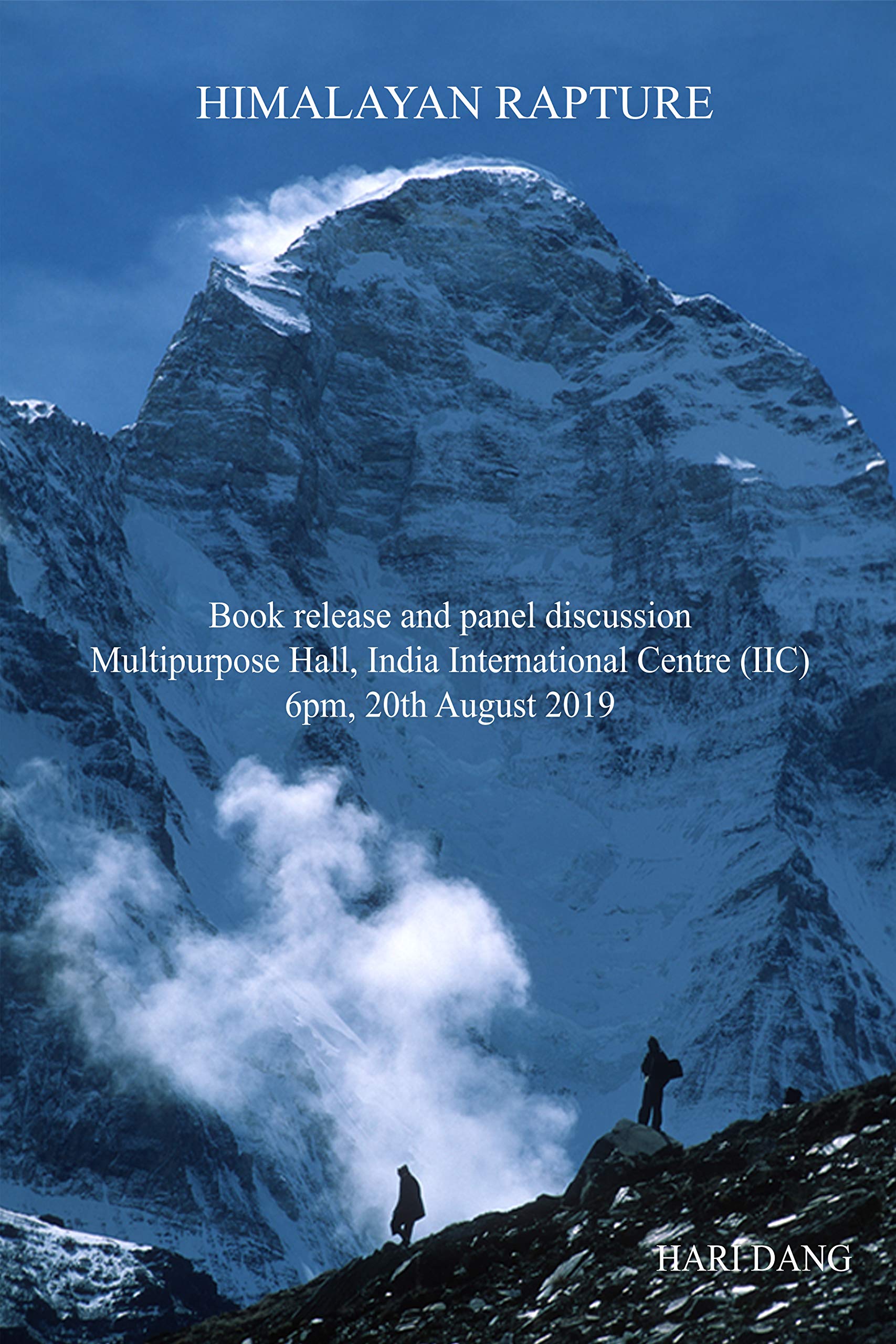

The Himalaya over millennia has hosted deities, rishis, hunters, shepherds, cultivators, pilgrims, and mountaineers, but in our heavily polluted age today, its overarching benevolence is almost narrowing to the last gasp, as the luxury of breathing in rejuvenating mountain air and drinking the elixir of mountain streams shrinks. One literary talent who perceived the crucial link between inspiration and the benefits of breathing mountain air was Hari Dang, who forcefully endorsed the traditional Indic feeling of reverence for the range.

Attuned to life’s poetry, Hari Dang as climber, shikari and educator, at the Doon School, Dehra Dun, St. Paul’s, Darjeeling, and the Air Force School, New Delhi, was an inspiration to over a generation of students, whom he encouraged to question received wisdom and embrace the challenge of the outdoors. His outgoing personality tended to conceal the lyrical sensitivity revealed in Himalayan Rapture; this selection of their father’s writings published by his sons comes as a welcome riposte to the disdainful attitude of eminent Victorian surveyors concerned more for imperial prestige than Indian veneration.