To be single by choice is not seen as choice. A few women I knew were kept single by their fathers so that the salary they brought home could provide for the son’s education. Others were promoted to the status of sons providing for the siblings’ marriages and the welfare of their parents first with pride, then confusion and then resignation. Some of these women married late in life, found husbands who valued them and provided the tender care and respect that fell through a gap in parental homes. I remember admiring one scientist who was single and she said in a matter of fact tone that maybe the women were not lucky enough to find the right partner. I remember I was shocked at the clay feet of my idol. For many women marriage was also an escape from the parental home which was more often not as ideal as it is made out to be. I also remember arguing at one point that ideally a woman should, like Draupadi, have five husbands. One to read and argue with, one to travel with, one to raise children and mind parents with, one to dream and star gaze with and one just to go to bed with!

To be single by choice is a luxury and also a question of class, when the precise moment of choice appears seems hazy. But to have a family that respects your work, your will and your capacity to stand on your own two feet is a great thing.

Continue reading this review

Every piece in this volume is refreshing and different. After writing about single women, all remarkable, all famous, who had survived the loss of their long-time partners and continued to build the rest of their lives brick by brick burying their grief—reading this collection was in a sense like walking through the looking glass and again perhaps not. The assumptions made about single women’s needs, unmarried or widowed, have a striking similarity unless there is strong family support.

To marry, or not to marry, that is the question. Whether to take arms against the sea of family and struggle with its endless demands and survive as a human being or to turn away and swim against the tide to find that it is empowering and fulfilling. That work well done, that having a family and community extending beyond the traditional, can be deeply satisfying. Each of the women in this volume are remarkable achievers. Bound to the communities they work with. And enjoying the independence of being single. Laila Tyabji points out that as the compromises and adjustments of marriage seemed more and more claustrophobic, the idea of a lover who lived down the lane seemed bliss. She points out that while stereotypes change, the fondness for the stereotype does not. So a single liberated girl must be wildly promiscuous. And while she balked at the thought of single motherhood, she found a daughter late in life enjoying the joy of motherhood. And strikes a warning note saying that while life is a lengthy process, one should make it fulfilling and fun and not a cage. And that is a warning note that recurs in all the voices that life should not be allowed to cage us.

Bama’s account is poignant and honest as she traces her painful journey into a convent and out finally focusing on teaching as the most productive thing she can do while she pounds out powerful novels that capture in graphic detail the life of a woman who is Dalit, single and stubborn. It also reminds us of how inviting and safe a nunnery seems until the seams begin to split. The single woman has always been an object to be exploited and abused by family and community until feminism actually realized that this was a category to focus on. Sujatha Patel painstakingly analyses the choices and the hazards of the single professional. She takes apart each aspect laying bare the public attitudes and prejudices about single women who are successful.

Freny Maneksha asks why marriage seems to be the only marker of adulthood. And about learning that one is not incomplete, adhuri nahin, from a rural woman. And how without waiting for a Prince Charming or a frog to kiss to complete their lives they went ahead and lived it well with meaning and dignity. Asmita Basu points out that the domesticity of relationships forges similar patterns. The single woman poses a threat to this ordered patriarchy. And that aloneness and singleness are not matter of choice. And just as there is more to marriage than companionship there is more to singleness than being alone. That is a nugget to store.

Vineeta Bal points out that without a clear vision of gender politics it is impossible to think seriously about change. She says that it was rare to find a never married scientist in the science gatherings and many who were married stayed out and lost out on career. She adds that shouldering household responsibilities did create hurdles in women’s careers.

Rhea Saran declares that as a woman of the twenty-first century, her definition of a successful romantic relationship and of marriage would be partnership in the true sense of the word.

One of the most delightful pieces in this book is the one by Aheli Moitra. The warmth and humour and clarity of that piece has to be enjoyed first hand. Sharanya Gopinathan’s ironic insights delight and tickle one’s sense of humour.

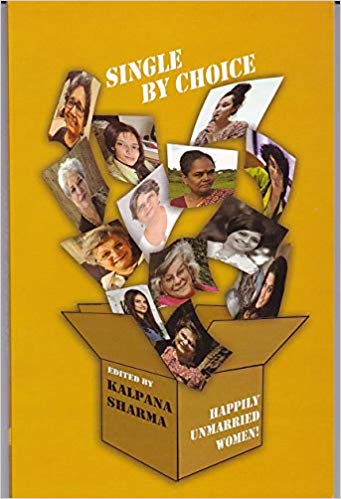

On the whole, a book well worth reading. Kalpana Sharma has by waving a wand framed a category. One of choice and a way of life.

Vasanth Kannabiran is a writer and activist who has been working on issues of women’s rights and communal harmony. Associated with Asmita Collective she lives in Hyderabad.