Aside from the reflections of India’s first psychoanalyst, Calcutta-based Gindrasekhar Bose (1886-1953), made famous via his correspondence with Sigmund Freud, contemporary Indian psychoanalysts have been fairly unanimous in finding the clinical work of their colonial counterparts un-creative.

The constellation of factors responsible include the early psychoanalysts’ deferential awareness of the origins of psychoanalysis in the West, food shortages and economic difficulties in Calcutta following the Second World War, and perhaps most crucially, an impediment to critical thinking caused by the presence of British army officers at the meetings of the Indian Psychoanalytical Society.

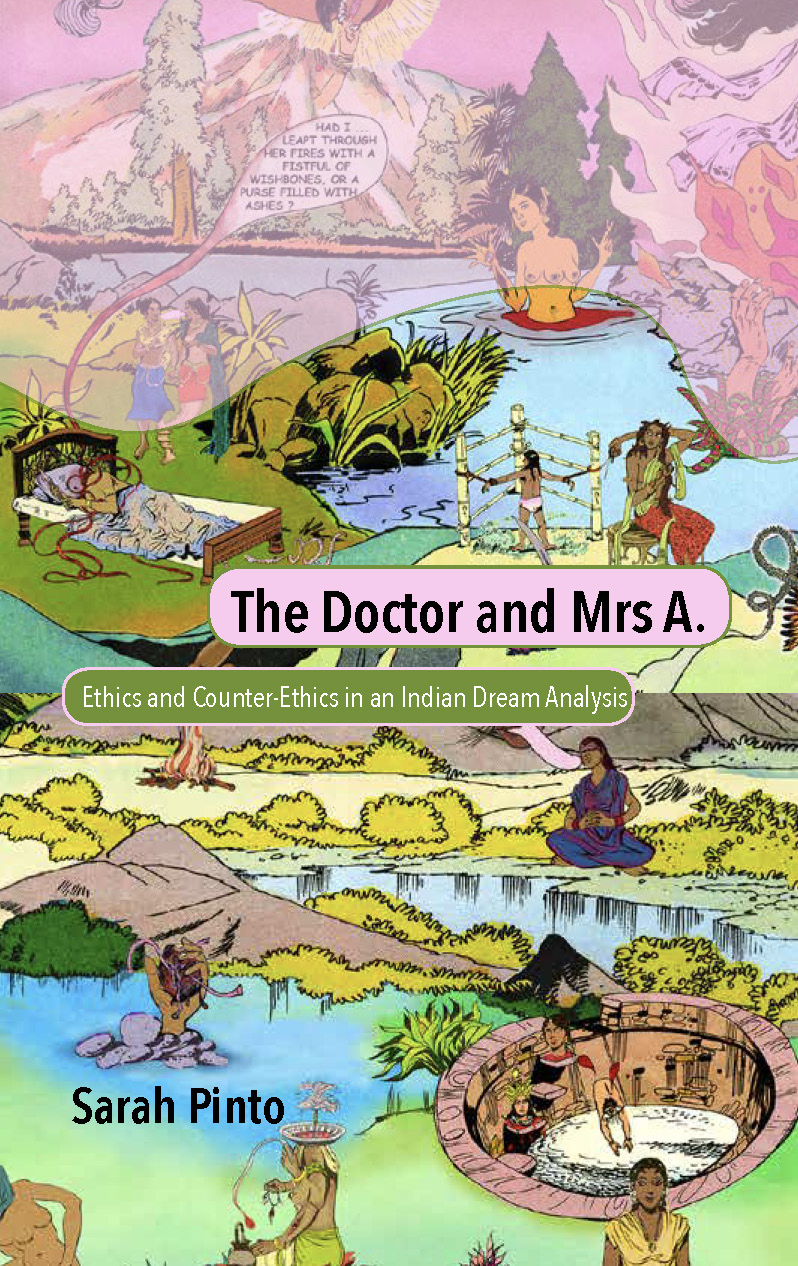

The British army officers served as a liaison between the Indian Psychoanalytical Society and the International Psychoanalytic Society; notorious among them was an army officer known as Owen Berkeley Hill, whose racist and orientalist readings of Indian patients and culture were published in international journals, replete with the rampant misuse of psychoanalytic theories to maintain the colonizer-colonized status quo. So when I read that Massachusetts-based anthropologist Sarah Pinto had discovered at NIMHANS Bangalore, a promising 1947 publication, written by one of Owen Berkeley Hill’s Indian trainees, Dev Satya Nand, a military psychiatrist and psychoanalyst, my interest was immensely piqued.