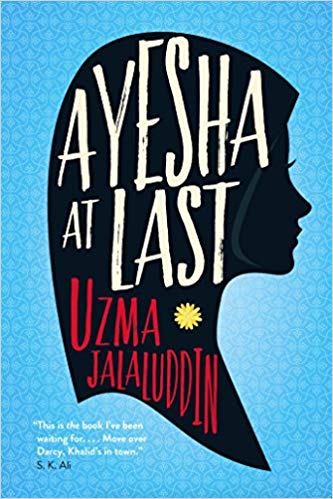

Uzma Jalaluddin’s Ayesha at Last is an interesting novel about the way Muslim social life is lived in Canada. The language used by Jalaluddin, though crisp and current is also loaded with an English literary sensibility. Shakespeare is quoted eleven times from the plays and twice from the sonnets. The blurb on the book describes it as a ‘modern day Muslim Pride and Prejudice’ nudging the reader softly to accord the novel a recognizable space in the ever expanding universe of English fiction being written across diverse cultures. However, as the novel struggles to keep the narrative racy and enjoyable in the manner of Jane Austen’s novels about love and match making in a society where class and gender form important parameters, does it also not raise questions of identity and its markers in a globalized world? Would it not be a simplification to regard the novel merely as an attempt to write a story about trying to find the right life partner, the only difference being that the central characters wear hijabs, or gowns, sport beards and wear skullcaps (if male); they go to the mosque to socialize instead of attending seasons at the court?

By negotiating the discursive determination of Muslim female as well as male identity in Canada, the novel destabilizes monolithic assumptions about Muslims in the so-called first world. Ayesha at Last opens with the male central character, Khalid, staring, read ogling, at Ayesha, the ‘almost thirty’ female protagonist of the novel from his bay window. She wears a purple hijab and a blue button down shirt, blazer and black pants, and is running down the steps of a middle class townhouse, a red portable ceramic mug (presumably of coffee) in her hand. She seems to be in a tearing hurry to get into her car and drive off to work. Uzma Jalaluddin gives you several witty take offs at places in the novel, the first being the thoughts passing through Khalid’s mind, ‘It is inappropriate to stare at women, no matter how interesting their purple hijabs.’ The quoted line is in italics in the novel, slipping in the description of the ‘purple hijab’ without raising any eyebrows. The novel points at what Bhabha calls ‘hybridized subjectivity in the third space’, which helps to explain how individuals negotiate the contradictory demands and polarities of their lives. However, it could also be that Uzma Jalaluddin is attempting to do just the opposite—trying to overlook, or even erase the polarities and contradictions by ‘normalizing’ the discourse about Canadian Muslim bearded men and hijab clad women who wear western clothes and eat fries which are supplied with assorted seasonings in the food courts of Canadian malls. The novel certainly has moments when the Canadian/American life is made to blend with wearing hijabs, caring for grandparents and offering namaz at the local mosque, which is more a hub of social activities than a congregational place of worship. The difference of worldview however, is not something that Jalaluddin overlooks. The first chapter of the novel ends with the lines: ‘While it is a truth universally acknowledged that a single Muslim man must be in want of a wife, there’s an even greater truth: To his Indian mother his own inclinations are of secondary importance.’

Any reader with above average interest in English literature will immediately recognize the echoes of the opening lines of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. In addition, she will also not fail to notice that Indians may have an entirely different view about the right to choose that ‘wanted’ husband or wife.