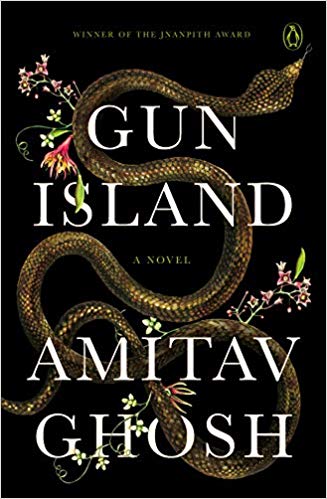

Amitav Ghosh seems to have reached a new point of eminence in his creative journey with Gun Island. In 2016, he published The Great Derangement—a book that deliberates on climate change and examines how collective denial of it is obfuscating our desire to address questions related to drastic fluctuations in the weather pattern. He emphatically concludes that art and literature of our age function in ‘modes of concealment’ and occlude everyone from ‘recognising the realities of their plight’. Gun Island (2019), is a bold attempt to make amends in which, in his inimitable flair and literary flamboyance, Ghosh introduces themes of catastrophic changes in climate, and migration of humans and animals, by conflating time and space through the depiction of Sundarbans, Los Angeles and Venice. At the same time, Gun Island blends ancient realms of myth and heroic journey with the modern world and the crises it faces; it juxtaposes memory and folktales by commenting on the importance of remembrance and storytelling, and imparts a lesson on love and reconciliation through the portrayal of relationships that stretch across countries, continents and seas.

The central character of the novel is Dinanath Dutta, hailing from a second generation Kolkata-based Partition family, who is now settled in Brooklyn and sustains himself as a dealer in rare books and Asian antiquities. He prefers being called ‘Deen’ rather than Dinanath, and with ‘sixties looming in the not-so-distant future’, he negotiates with his loneliness by visiting a therapist and amateurishly investing in stock markets and life insurances. Life takes a different turn for him during one of his visits to Kolkata where he encounters Kanai Dutta, one of his distant relatives. It is interesting to note that Kanai Dutta is a familiar figure because Ghosh resuscitates him from one of his previous novels, The Hungry Tide (2004). We are made aware of the fact that Deen holds a Doctoral degree in Bengali folktales. Hence, when presented with the opportunity of following an intriguing story of one Bondhuki Sadagar—the gun merchant, Deen decides to visit a shrine in Sundarbans dedicated to the gun merchant’s feud with Manasa Devi, the Snake Goddess. In what ensues, a series of somewhat unconnected but fascinating occurrences take Deen from the swampy, uninhabitable mangroves of Sundarbans to ash-ridden Los Angeles and thence to Venice with its Bengali speaking quarters, mainly migrant workers from Bangladesh and Bengal.

The book is divided into two segments: ‘Gun Merchant’ and ‘Venice’. In the first section, we encounter Tipu who has matured in age and vitality from the child that he was in The Hungry Tide. At the shrine, he gets bitten by a King Cobra, and this particular incident sets the novel in motion. His histrionic behaviour informs the narrative as he provides glimpses of what is about to unravel in the pages to follow. Furthermore, Tipu is an embodiment of the charismatic tech-savvy youth who refuses to believe in borders, passports, visas and permits. His is a world of extraordinary alacrity where his breathless spirit interrogates established notions of family, love and life. All of it has to do with his father’s untimely demise that is mentioned in passing by Piya in the later stages of the novel. It is through Tipu, and later Rafi, that Ghosh explores the theme of migration. Through observational narration, Ghosh coalesces the bits and pieces of a migrant’s life and helps the readers comprehend what migrants experience in an unfamiliar setting. The erudite Italian professor, Cinta, provides a new lease of life to the story. If Deen willingly embraces scepticism and stands obverse to anything but his present reality, it is Cinta whose erudition and charm allow for a belief in foreordained facts and visitation from the dead. While in Los Angeles for the conference, Deen confides in Cinta about the story of the gun merchant, and Cinta, in what perhaps is one of the most moving passages, instructs him, saying that one ‘mustn’t underestimate the power of stories’. For it is ‘only through stories can invisible or inarticulate or silent beings speak to us; it is they who allow the past to reach us.’