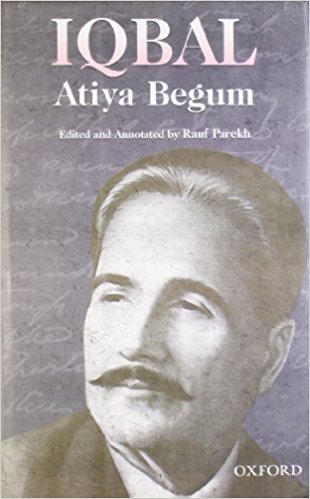

A slim 47-page booklet forms the kernel of this book; the rest is mere padding in the form of introduction, appendices and notes. However, the 47 pages of Iqbal contain much that is illuminating and useful—not merely about one of the greatest poets of the Urdu language but also about his age and many of his peers. Equally important is the insight Iqbal provides into the mind of a remarkable young woman. Atiya Fyzee, daughter of Hasan Ali Effendi and Shareefunnisa Tayabali was born in Constantinople in 1877 with the proverbial silver spoon in her mouth. Unlike other well born women of her age and station, she chose to hitch her star to the great intellectual discourses of her time and used her wealth and status to broaden her horizon in a manner that had never been attempted before by any other Muslim woman in this part of the world. Educated in England and Germany, Atiya travelled and read extensively. She derived the benefits of the new western-style education yet deplored the loyalist overtones of its most vocal proponents. By far the most stylistically sophisticated poet of the twentieth century, Iqbal drew on the best resources of a liberal western education.

Upon graduating from the prestigious Government College, Lahore, in 1899, he worked as a lecturer in philosophy at the same College, went on to study philosophy at Trinity College, Cambridge and in Heidelberg and Munich in Germany, eventually appearing for the Bar-at-Law from 1905-1908. While in his early poetry he had spoken of a united and free India where the Hindus and Muslims could coexist, this belief in syncretism and pluralism soon gave way to unitarianism and individualism. The Tarana-e-Hind (Ode to Hind) written in 1904 was followed by the Tarana-e-Milli (Ode to the Religious Community) in 1910 showing the progression from Hindi hain hum watan hai Hindostan hamara (We are the people of Hind and Hindustan is our homeland)to Muslim hain hum watan hai sarajahan hamara (We are Muslims and our homeland is the whole world). The ‘sweet madness’ (shireendivangi) of his early poetry gave way to a ‘divine madness’ (muqqadasdivangi). The simple lyricism and romantic nationalism of the early phase was replaced by a certain self-conscious prophetism tempered with a strong political and social undertone. Why this change happened and what in the poet’s personal life could have contributed to this change has been the subject of much debate among Iqbal scholars.