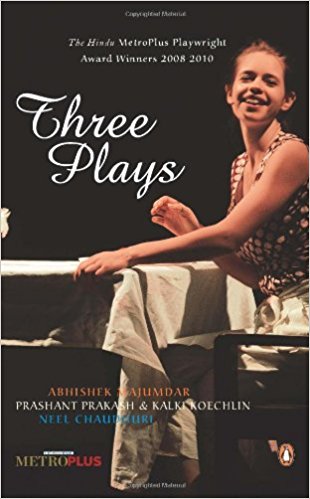

The bountiful nature of the publishing business in India in recent years has brought tens of new voices writing in Indian English to the bookstores and bedside tables. Not all of this mishmash of themes and writing styles makes for great reading, and almost always the blame lies in for pretentious, uninspiring writing. But the Hindu Metroplus, with its Playwright Awards has taken the initiative to encourage original writing in Indian English theatre and struck gold, as evidenced by Three Plays, a book of their winner’s works from 2008-2010, published by Penguin. Those acquainted with English theatre in the country will have noted at some time or the other that fresh voices writing powerfully is certainly one of the needs, if not the need of the hour. Four writers, all of them from the newer generation of writers have won the award for Best Play. Abhishek Majumdar gives us Harlesden High Street, a poetic, passionate piece about a Pakistani family in West London. Prashant Prakash and Kalki Koechlin together script The Skeleton Woman, a surreal and engaging play about a writer and his inner demons.

Neel Chaudhuri turns Satyajt Ray’s short story Patol Babu Filmstar into his power punch of a play, Taramandal, about a nobody who gets a walk on part in a film late in life.