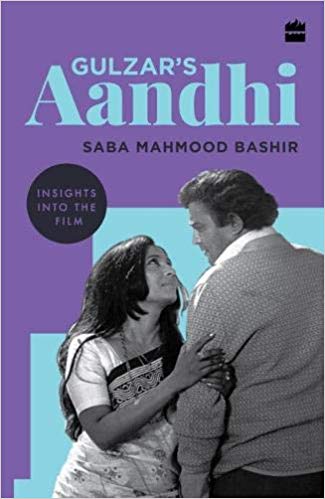

This is a slim book, choosing to focus on only one film: Aandhi. Made by Gulzar, it was released in 1975, a momentously significant year for India and for the Hindi film industry which sent to the theatres, one after another, movies such as Deewar, Sholay, Aandhi and Mausam, even as Emergency was declared during the month of June.

In ‘The Controversy’ Bashir incorporates a brief discussion of the decade and the political and economic reasons that led to the precipitation of the theme, amongst others, of the angry young man interrogating the system. During the course of her rather slender discussion she makes fleeting references to academic studies on this topic in particular and Hindi cinema in general by well-known scholars including Partha Chatterjee, Vinay Lal, David Lockwood and Sumita Chakravarty. The references are apposite, yet the connections to their arguments are neither pursued at length nor with any vigour, in the process letting the examination of the film in the book subside to well-worn and clichéd simplifications.

It is this logic that operates in the manner the book is structured. Divided into five chapters, ‘The Auteur’ examines Gulzar’s cinematic oeuvre before attempting a short synopsis of the subject of the book: the film Aandhi. It does not help that this remarkable poet’s wide range of songs across several decades of writing for the Hindi film industry finds brief and simplistic discussion under heads such as ‘love songs’, ‘political satires’, ‘songs for children’ and ‘philosophical songs’. The second chapter as seen above focuses on the 70s, as well as on the controversies that followed the film’s release. Largely these erupted in the wake of a perceived similarity between the life and persona of the female protagonist of the film with those of Indira Gandhi, which resulted, in the year of the Emergency, in a ban being imposed on the film. While this chapter has some glimmers of the shape of the book as it may have been, ‘The Stellar Cast’ crashes the readers’ expectations through its cringingly naïve accounts of the actors in the film and their roles, the summaries of which seem hopelessly like ‘character sketches’ reminiscent of school essays. ‘The Poetry’ explains the four songs in the film and how they are picturized; the last chapter attempts to summarize the film’s dialogues and their wit, sensitivity and humour.