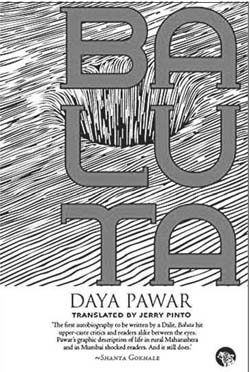

Rohith Vemula’s hanging body; Soni Sori’s swollen face; Kawasi Hidme’s ejecting uterus; Monisha, Priyanka and Suranya’s floating bodies—all have one thing in common—these are Dalit bodies. Living or dead, their faces, uterus, eyes, hands and feet are first Dalit, then parts of a human body. This raises a crucial question: how can a human body, an anatomical subject formed of cells that are always dissolving, regenerating and growing, embody something as non-biodegradable as caste? In other words, how can a face, a uterus and a lifeless body be first Dalit, and then be human and acquire a species-identity? Isn’t our corporeality the most inalienable part of our selfhood? Or does caste as a denominator far exceed our claims to a shared history as a species? These questions plagued me until I read Daya Pawar’s Baluta. Published first in Marathi in 1978, Baluta forces me to recognize the following: caste has pernicious effects not because it is a political, social or a cultural designation. More threateningly, caste is a visceral experience, marked on our bodies, through the acts of speaking, eating, sleeping, and love-making. And while our bodies may die, decay and be erased, caste remains non-biodegradable and cannot be dissolved.

The strength of Baluta lies not in providing an alternate critical position to this visceral experience of caste; in fact, the novel eschews any possibility of an alternative. Baluta’s strength lies in laying bare a reality where mining for an alternative is in itself a revolutionary idea. Pawar achieves the slipperiness and pervasiveness of this fraught reality with the use of two voices; one, of an educated-self who is listening, reflecting and trying to find a way beyond the life of a Mahar, and second, of a self who is never able to move beyond his Mahar caste and is angry and dejected. If the former is retrospectively producing a narrative of his own existence, the latter is constantly interrupting, ranting about his more urgent needs. Thus, Pawar moves precariously between an author, a narrator and a protagonist. Instead of a coherent narrative voice, Baluta therefore offers moments of heterogeneous voices. The reader is left to grapple with a range of perspectives—is Pawar critiquing the Hindu-Brahmanical structures when he opts to be educated; is his love for Ambedkar’s writings a critique of the ‘universal’ human values that devalue the Mahars; then why does he silence his grievances to achieve that education; is his silence a self-complacency that re-situates caste as a burden that cannot be unloaded; how can there be any politics of alterity when Pawar is self-consciously violent and misogynistic towards the women in his life? Pawar does not answer any of these questions. Instead, his two voices constantly jostle, argue and scramble. The reader must mine the meaning out of these competing voices in the novel.

Thus, the reader is caught in a spiralling circuit of events—events that enabled Pawar to become an author, acquire a narrating voice and be a protagonist. Because Pawar attempts to separate these distinct identities as well as consolidate each as his own, his autobiography becomes about the struggle to be unique and individualized, and be a voice of the Mahar community. Baluta, like Pawar, becomes deeply invested to shore up meanings which are both ineffable and discrete. As a result, Baluta does not offer a radical critique, but a careful unpacking of the conditions of (im)possibilities that Pawar encounters to be an author, a narrator and a protagonist.