Writings by Adivasis (ecriture) which have emerged in India during the last three decades mark an important milestone in the context of the cultural expression of Adivasis hitherto found only in the oral-performative tradition (orature). These writings are markers of identity assertion and cultural activism by educated Adivasis who want to write about themselves in their own words to combat their degraded or exoticized depiction by non-Adivasi writers. One needs to read Narayan’s interview (Kocharethi, OUP, 2011, 208–16) to realize why educated Adivasis are prompted to pick up their pen. What happens when a medical officer picks up his pen to write stories? Read through these hard-hitting, in-your-face stories and you know what the outcome is. Written by Hansda Sowendra Shekhar, a medical officer with the government of Jharkhand, this collection of ten short stories which as the blurb announces ‘is a mature, passionate, intensely political book of stories, made up of the very stuff of life’. These agonizing stories assault the reader ‘like a thin rubber band which snaps as one is tying a chignon, and stings the fingers’, as Shekhar describes Basanti’s plight in the story ‘Baso-jhi’ (p. 119).

Shekhar mentions in the ‘Acknowledgements’ that eight of these ten stories ‘were first published in different forms and in some instances with other titles, in various periodicals’ like La. Lit, Northeast Review, The Four Quarters Magazine, The Statesman, Indian Literature and The Dhauli Review. Cobbled together in the avatar of a collection the stories present a kaleidoscopic view of the traumatic life of the Santhals on their native soil and beyond, some of them in an exclusively rural or urban setting and some at the intersection of urban and rural existence. Most of the stories depict the interaction of the Santhals with the ‘Dikus’, the outsiders, on a day-to-day basis. And the experiences that the Santhals have, as a community or as individuals, as men and as women, are steeped in discrimination on the basis of socio-economic status, ethnicity and gender, social, economic, cultural exploitation in the general context and sexual exploitation in the particular context of women.

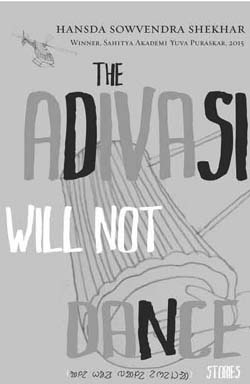

The first story ‘They Eat Meat’ and the last story ‘The Adivasi Will Not Dance’ form a pair with socio-political ramifications which are extremely relevant in the present context, especially when divisive forces are posing a grave threat to the diversity and plurality which define our country. Aunt Panmuni-jhi in the first story who while in her village outside Ghatshila near Bhubaneshwar ‘would avoid eating out, fearing infection and stomach upsets’ and ‘so paranoid was Panmuni-jhi about eating restaurant food that her tummy would begin to rumble a warning even before she had put a morsel into her mouth’. Well, it is only natural that after her husband Biramkumang was transferred to Vadodara in Gujarat, one of her immediate concern was food. Her apprehensions started to prove themselves from the time she contacted her cousin Jhapan-di who lived in Vadodara as her husband, working with the Central Industrial Security Force, was posted there. Panmuni-jhi learnt that ‘where to stay and what to eat’ would be a problem, that the food habits there were ‘very different’ and that she may ‘have to stop eating quite a few things’. Her world came crashing down when Jhapan-di announced, ‘people don’t eat meat here. No fish, no chicken, no mutton. Not even eggs’ and that ‘people here don’t like to mix with those who eat meat and eggs.’ (Emphasis added) Food based discrimination is as rampant as other forms of discrimination in our country is the message conveyed by the story.