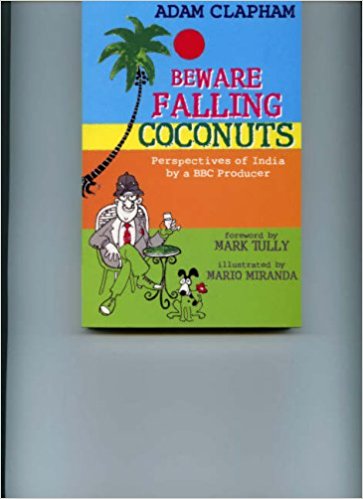

Robert Clive is said to have ‘gone native’ in India, sitting on a charpoy, puffing a hookah, dusky ‘bibi’ by his side, watch-ing the fascinating, multifarious world of the subcontinent go by, so much more vivid and intense than the cold, drear monochromatic little island that he came from. Clive was, of course, a robber baron and a proto-imperialist, a ‘savage old Nabob with… a bad liver, and a worse heart’, as Macaulay, no slouch at empire-building himself, was to call him. But Clive has had benign avatars in latter-day Englishmen who, having come to do a job of work in the erstwhile Jewel in the Crown, have fallen under its Circe-like spell and elected to stay on, lounging on metaphorical charpoys, to watch the passing show, the cavalcade of lively contradictions that is India: vulgar wealth and grinding poverty; politicians so full of pious pomposity that it’s a wonder they don’t float up and away like hot air balloons; the round-eyed ingenuity of illiterate village folk that masks an educated canniness which would do a PhD in Political Science proud and which is made painfully evident to smug candidates on election day; ambling cattle and occasional elephants and camels negotiating right of way on anarchic roads with Marutis and BMWs and Bajaj scooters in a graphic representation of how the world’s most populous democracy works; the ubiquitous street dog, enduring symbol of survival against all odds, lifting an irreverent leg against a streetlamp, temporarily out of order thanks to a power cut.

July 2007, volume 31, No 7