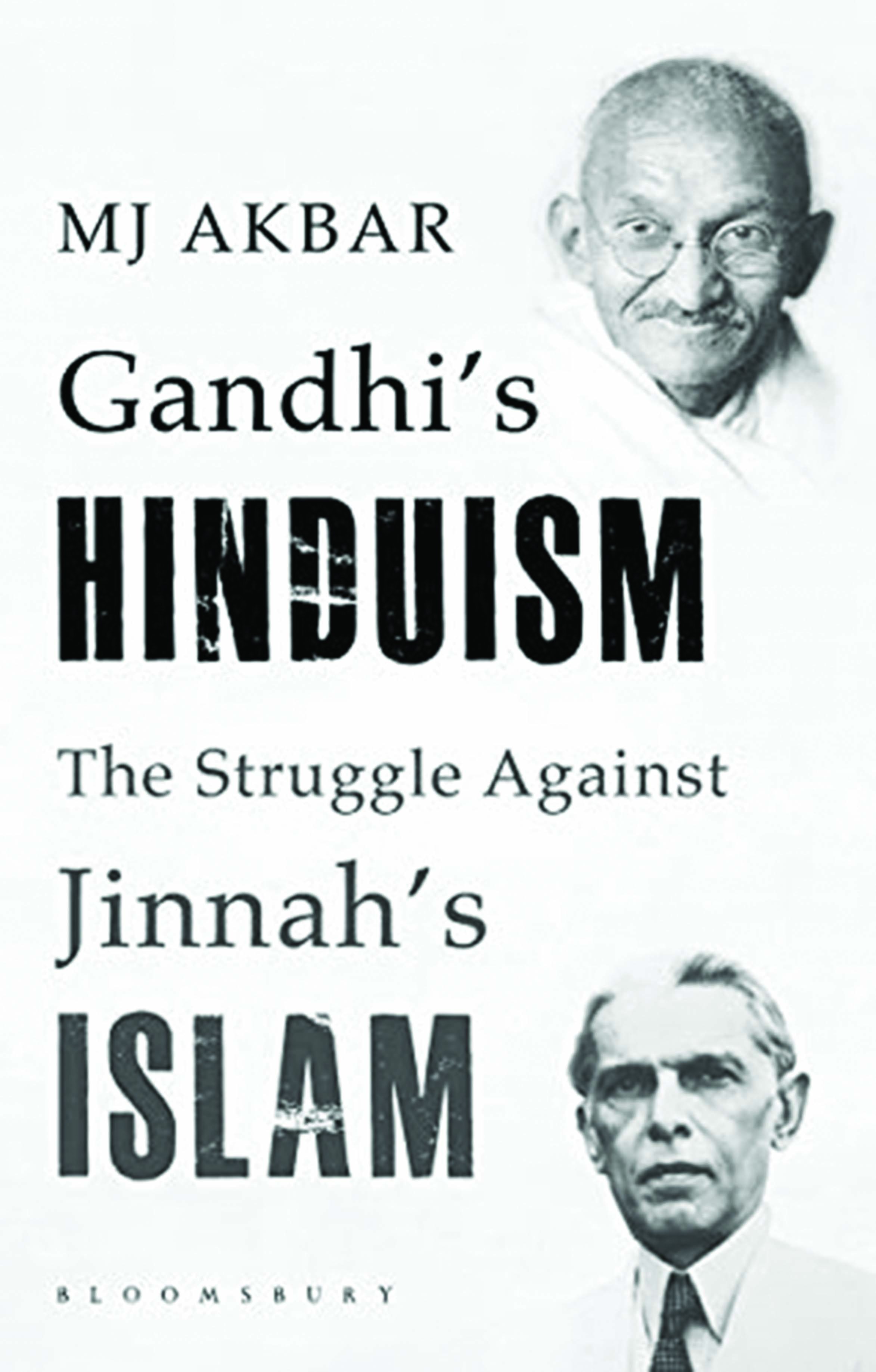

MJ Akbar needs no introduction. A famous journalist and politician (BJP), he is also a prolific writer. His latest offering, its unwieldy and somewhat misleading title notwithstanding, is about the last phase of India’s freedom struggle. The struggle for freedom was never between Hinduism and Islam, not even in its last phase, no matter how loudly the British said it was so. The struggle was always between Indians of various hues on one side, and the British + ‘Mussalmans of Importance’, to use the phrase Lord Minto used for them, on the other.

The story is as tragic as it can get. Because everything went wrong between 1940, when Jinnah first made his call for Pakistan, and 1947, when he got Pakistan, a million and a half people died a horrible death, lakhs of women met a fate worse than death, and fifteen million terrified people were forced to flee from their homes with little more than the clothes on their backs and bitterness in their hearts. Less than six months later, Gandhi, who had opposed the ‘vivisection’ of India till the last, was killed (by a Hindu). A few months later, Jinnah, consumed by a wasting disease, died inside a hot, stalled, ambulance on a desert road with just his sister Fati by his side, struggling to keep flies away from his face.