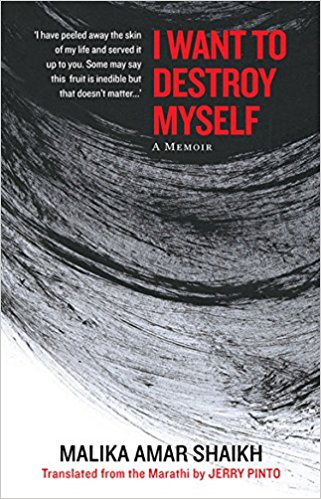

Here was a pinkish-red staircase, and a small piece of sky and the white fairies of delirium and the handsome prince who would visit me and tease me. I have peeled away the skin of my life and served it up to you. Some may say this fruit is inedible but that doesn’t matter

I Want To Destroy Myself (Mala Uddhvasta Vhaychay) by Malika Amar Shaikh, now translated into English by Jerry Pinto, shows her growing up as the pale but intellectually rigorous second daughter of Amar Shaikh, the Communist Party worker, and, then as the wife of Namdeo Dhasal, the Dalit poet. Shaikh’s life-story begins with an almost-idyllic childhood, followed by the death of her father and marriage to Namdeo Dhasal, and then becoming a narrative of pain and suffering.

Throughout this constellating tale what remains constant is Shaikh herself—an autobiographical subject who is graphically represented as a female in pain, a writer who is suffering and thereafter recording each moment of pain. Shaikh’s life-story focusses on her pain, and Jerry Pinto as the translator says that: ‘I wept for the young woman with the endless meals and floors and nappies, for the boils and also for the kindness of strangers. It’s that kind of book’ (p. 11). Both Pinto and Shaikh remind the reader to recognize the autobiographical subject as a human in pain, a suffering self from among other possible self-representations. That all other representations quickly fade away and the reader sees only a female writer living in agony testifies to the inherent pull of pain—pain draws inward. Pain functions as a discourse.

Most autobiographies by Dalit men and women are testimonies of their painful lives and portray the gradual evolution of the writing subject. Pain acts as an agent of change, and the triumphant autobiographical self is linear, progressive, and projects an identity that challenges the societal norms. Shaikh’s autobiography is unique because it does not tell the story of any victory. Unlike Shantabai Kamble, Baby Kamble, Kumud Pawade, and Bama, Shaikh tells a story about losing control of her body, her desires and dreams, and then withdrawing into her abject conditions so much so that she wants to destroy herself—as the title of the book suggests. If Dalit autobiographies emphasize the universality of their abject conditions, Shaikh strives to portray the specificity of her pain. In the process, Shaikh creates a very unique autobiography—a tale that is sad and minutely chronicles the impossibility of any triumph —hence almost an impossible text to be retold in another language.