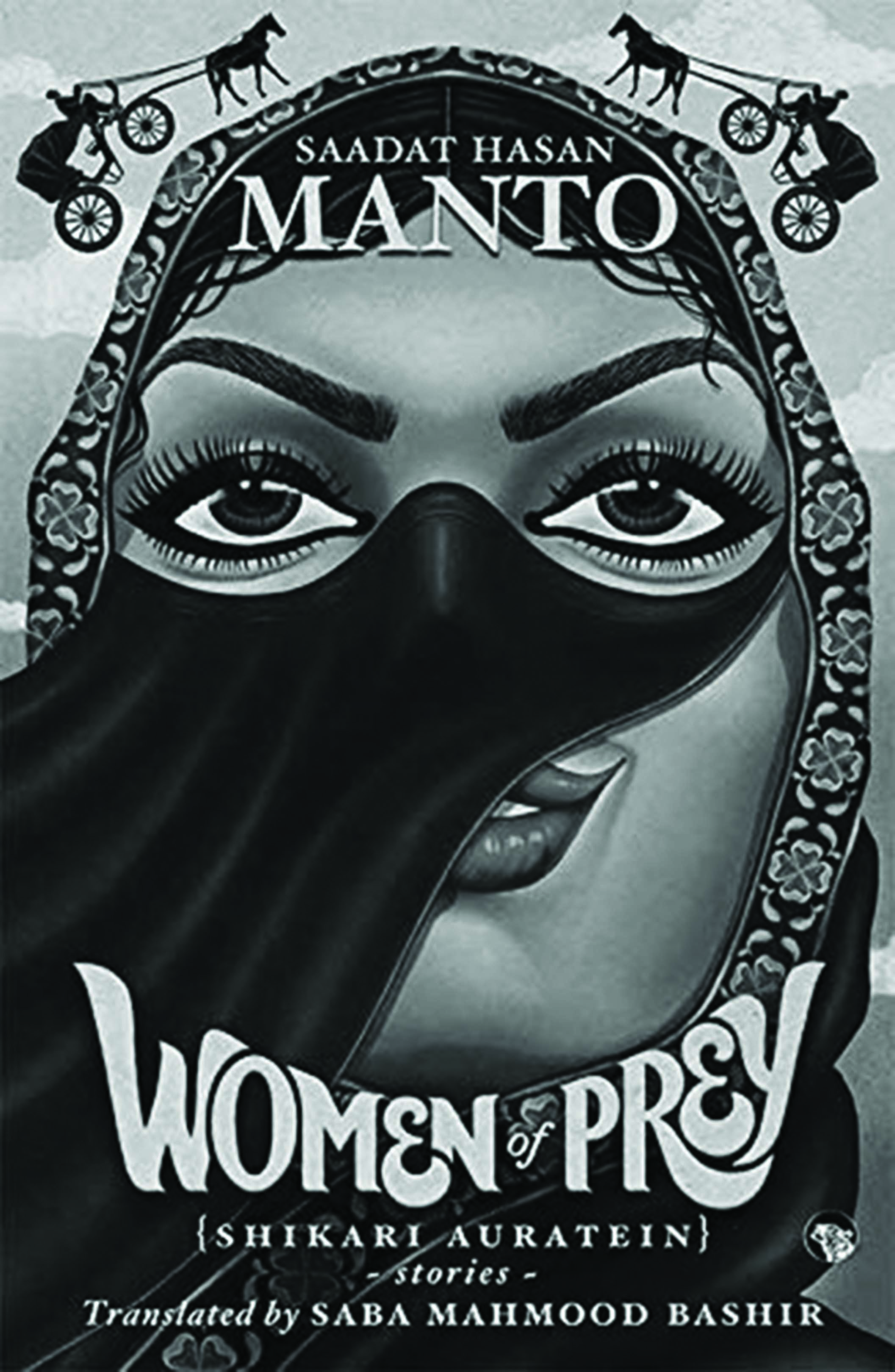

Capitalized SAADAT HASAN MANTO, printed against strands of jet black hair that have escaped the floral edge of a burqa, which reveals more than it conceals; arched eyebrows, large and thickly kohl-lined eyes, the partial tantalizing glimpse of painted lips; tongas on either side of the head, complete the picture. The finely detailed illustration, just described, is the cover image of Manto’s Women of Prey: Shikari Auratein. Designed by Jezreel Sarah Nathan.There could not be a more striking and imaginatively etched cover for a book with such a title. The image makes the title come alive, enough to trigger a ripple of excitement even in the casual browser. However, the fare offered within the covers of the book is not exclusively about predatory women. Published in 1955, Shikari Auratein is a collection of seven short stories and two sketches. The translation is by Saba Mahmood Bashir, an academic who teaches translation in Jamia Millia Islamia. For the many readers, for whom the name Manto represents iconic stories like Toba Tek Singh, Khol Do, and Thanda Gosht , the present collection will come as a definite surprise. In her introduction Bashir observes that the stories and sketches together, ‘…show a completely different side of Manto—raunchy, mercilessly funny and gloriously pulpy, even when they end in tragedy’ (p.10-11). It is not an observation that all readers will subscribe to. However, a vignette that she shares in the introduction is fascinating, as it provides an illuminating glimpse of not just Manto’s life, but also that mysterious force called creativity. Apparently, Manto was unable to pass the Urdu language examination, both in school and college, and ended up as a college dropout. This seems amazingly unbelievable, when read against his monumental literary output in that language. The information casually included, is noteworthy, as it provides valuable insight into the reality that academic performance is by no means a foolproof criterion for evaluating an individual’s calibre and potential.

A Romp Through Manto’s Bombay, Lahore and Amritsar

Catherine Thankamma

WOMEN OF PREY (SHIKARI AURATEIN): STORIES by Saadat Hasan Manto Speaking Tiger, Delhi, 2019, 159 pp., Rs. 299.00

April 2020, volume 44, No 4