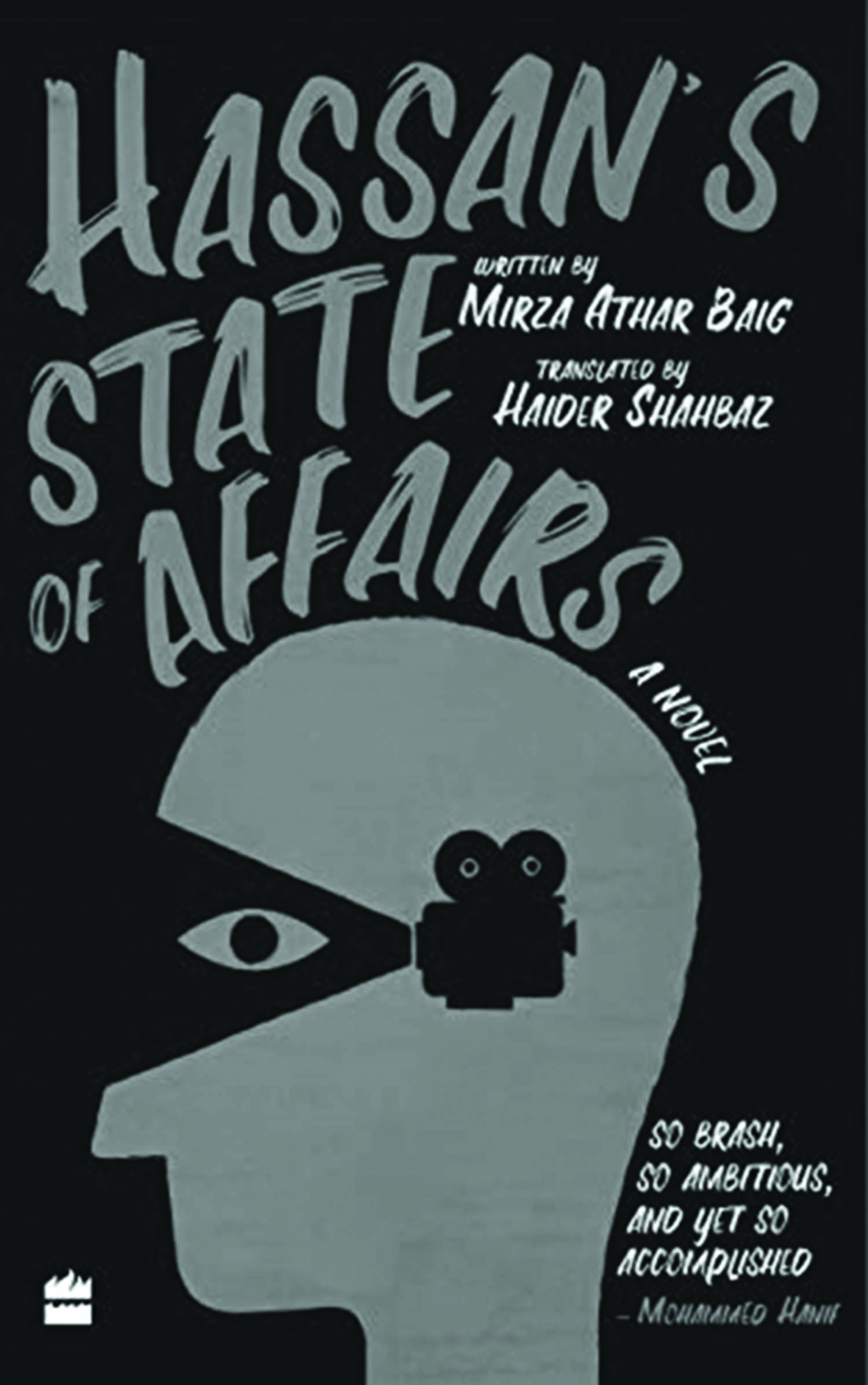

Urdu fiction is mostly known for its realist, humanist approach. Even in its most experimental incarnations, Urdu writers did not make any radical break from the modernist aesthetics. Mirza Athar Baig, a revolutionary in this sense, has been hailed as a pathbreaker who with each new offering has pushed the boundaries of Urdu fiction further. Born in 1950, Baig has been a teacher of philosophy at the Government College University, Lahore. Convinced of ‘immense textual and cognitive possibilities inherent in the genre of the novel’, Baig published his first novel, Ghulam Bagh in 2006, which created a sensation across the Urdu literary world. The iconic Urdu writer Abdullah Hussain, known for his magnum opus, Udaas Naslein declared in his preface to the second edition, ‘Ghulam Bagh is located vastly at variance with the tradition of the Urdu novel. The technique employed is rare even in English fiction.’ The novel, which as Mohammad Hanif points out, ‘achieved a cult status,’ was simultaneously viewed by some as ‘confusing rants of someone who has spent too much time teaching philosophy to Punjabi students.’ Baig’s second novel Sifr se Aik Tak deployed same techniques. His third novel, Hassan ki Soorat-i-Haal: Khali Jagahein…Pur Karein, was published in 2014. It is now available in Haider Shahbaz’s stupendous English translation as Hassan’s State of Affairs.

April 2020, volume 44, No 4