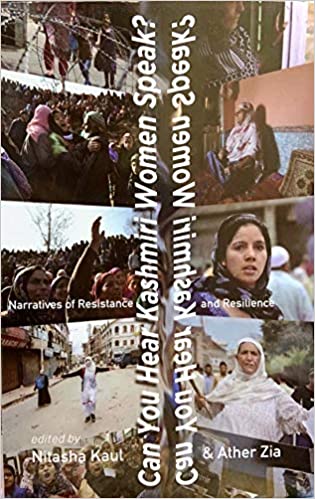

The ideational cohesion holding together this compelling collection of essays is driven by the need to visibilize the particularity of Kashmiri women’s ‘own ways of knowing’. The title Can You Hear Kashmiri Women Speak? Narratives of Resistance and Resilience announces that the experience of six decades of vulnerability, resilience and resistance to the ‘military occupation’ of Kashmir speaks differently to men and women. Editors Nitasha Kaul and Ather Zia explicitly privilege Kashmiri insider perspectives and posit a challenge to distorted statist narratives and myopic outsider analysis of gender in a situation of protracted militarized conflict.

Complicating this insider:outsider binary is that three-fourths of the contributors are part of the Kashmiri diaspora. Whereas this might invite problematization of the claim of representation given the refracted diaspora lens, academic Deepti Misri uncritically asserts the grassroots lineage of these ‘Decolonial Feminists’ whose provenance is the ‘Critical Kashmir Studies Collective’. Literary critic Asiya Zahoor, who stands out in this collection for her in Kashmir location, recognizes the liminal quality of diaspora writing as evinced in the context of Kashmir’s iconic poet, Agha Shahid Ali. She quotes the Libyan diaspora writer Khalid Mattawa to articulate that these diaspora writers by choosing to write or speak of their peoples are ‘alternately celebrating and resisting the burden of representation imposed on them by their own people and by the outsiders who receive them’.

Before I walk away from the title one teaser awaits. Who is the ‘you’ the essays address: transnational feminists or Indian feminists, Left liberal international or Indian civil society. Some of the authors, especially Deepti Misri explicitly differentiate between Spivak’s ‘appropriate solidarity’ and ‘transnational solidarity’ which requires Indian feminists to go beyond national boundaries. For instance, locating the kidnapping, rape and murder of an eight year old Bakerwal tribal girl not as a gendered crime but as a crime against a Kashmiri, Muslim girl and inextricably connected with the ‘militarisation, occupation and systematic use of rape as a weapon of war in the region’.