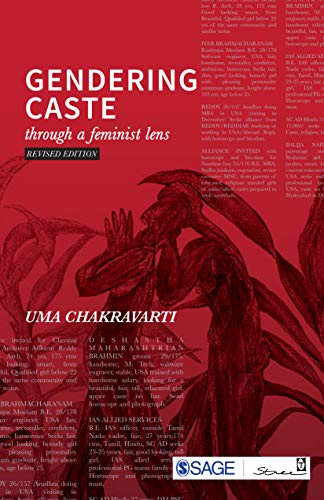

This is the revised and updated edition of a book originally published in 2003. Maithreyi Krishnaraj’s ‘Note from the Series Editor’ introduces the volume and places it in its context, while Uma Chakravarti’s ‘Afterword: Caste and Gender in the New Millennium’ provides a penetrating discussion on POA (Prevention of Atrocities Act, or more fully, ‘Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes [Prevention of Atrocities] Act 1989’. Together, they provide a valuable addition.

Uma Chakravarti’s book is an indispensable volume for students and scholars of both feminism and caste. The author explains why and how feminist theories and feminist perspectives in India have to be founded on two axes of women’s subordination: that of class, which is a universal axis of subordination, and caste, ‘a form of stratification unique to India’. This twin perspective undergirds Chakravarti’s analysis and her conclusions. The persistence of caste as a defining factor in the subordination of women, and its expression in the form of violence as a weapon of such subordination, forms a major theme.