Street theatre or nukkad-natak has a staccato rhythm. Those who have been part of it will know. There is no rule or convention within which it finds safety. It is both ephemeral and risky. Actors, audiences, the venue, the script, everything is provisional. Actors move in and move out like shadows. No star, no diva. The script is a shadow adapted and improvised according to context. The audiences too appear out of thin air, consolidate and then melt away into an anonymous void. The performance arena is not like some fixed proscenium with definite and impeccable proportions. It is a loosely demarcated space outside a factory, a railway station, a market square, a college, which can expand or contract even in the midst of a performance or dissolve completely at the hint of a storm or a passing procession or rally or get violently dispersed by the illegal arms of the law. The actors in this, particularly, are in a liminal space where their identity keeps forming, de-forming, re-forming in swift transitions. With the result no one has a face. Only their voice and their black, shadowy costumes.

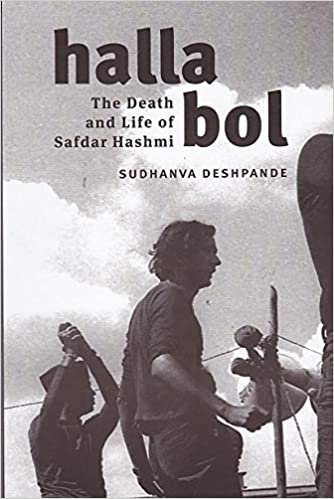

Safdar Hashmi was one such affective shadow in the theatre of the streets. It is thirty-one years since he was fatally attacked. Felled at the very site where he and his group Jana Natya Manch (Janam) were performing in the open, hardly 15 kms from the centre of India’s capital. Killed by goons of the ruling Congress Party. Attacked on 1 January 1989. Died on 2 January 1989. Yet, even though the light called Safdar might have been extinguished, his looming shadow—much to the consternation of the establishment against whom Safdar wrote and performed his plays—has remained. They have neither been able to get rid of him, nor been able to speak about him. They see his unspoken, critical presence in their elite shows. Despite draconian laws, physical intimidation and long incarcerations, Safdar’s shadow has haunted the powers that be for three decades. It is his shadow that the NIA saw when they went arresting Sagar Gorkhe and Ramesh Gaichor, artists of the Kabir Kala Manch, in September. It was his shadow at work in Shaheen Bagh as a courageous group of women performed resistance against erosion of democratic rights. It is Safdar’s shadow again out there at Singhu where the kisans are reciting, singing, performing. It is a shadow that is bound to trouble bourgeois national conscience for a long time.