Few other film-makers in the history of cinema could retain their creativity undimmed for as long a period as Ray did. From the time he started shooting for Pather Panchali in the early fifties till his demise in 1992 with many more films still in him, he had continuously changed course, renewed himself with new vigour, and directed his prowess in uncharted areas without losing his vision and distinctive style. The key to Ray’s sustained creative vigour perhaps lies in his statement to the author of the book under review: ‘Suresh, every film is like an adventure!’

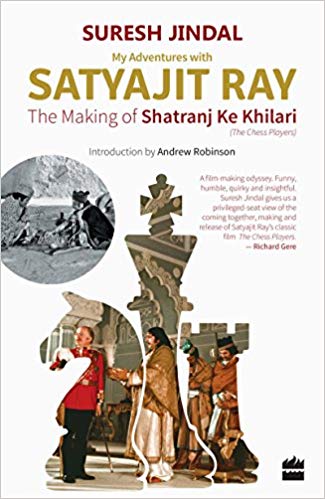

Suresh Jindal produced Shatranj Ke Khilari (The Chess Players, 1977) as he did some others like Gandhi. A young engineer educated in USA, he was smitten by the charm of cinema and took to producing films, and based on the success of his first film, dared approach the high priest of Indian cinema to direct a film. Fortuitous that he did so: Shatranj, based on a short story by Premchand, got made and as a by-product, forty years later, comes out this remarkable book. His adventures with Ray read with Ray’s adventure with the film are so rich, nuanced and delightful that the readers will get a distinct flavour of Ray’s mind as also interesting insights into the question of what constitutes the Ray-phenomenon. The book is more than a relationship between a producer and a director. About seventy letters exchanged between them form the soul of the book, throwing light on how art gets created, how the demands of cinema as a medium propel its maker to add new dimensions to the literary original.

Structurally, the book has been divided into ten chapters—starting from the initial encounter through ‘The Beginnings’, ‘Research and Scheduling’, ‘Casting’, ‘Final Preparations’, ‘Filming’, ‘Post-production’, ‘The Release and After’, and ending with ‘Looking Back’. To make the book comprehensive even to ones not familiar with Ray and his oeuvre, a brief biography has been included together with a Foreword by Jean-Claude Carriére, the noted French writer and film-maker and an Introduction by Andrew Robinson, renowned British author and Ray-biographer.