No chains around my feet But I’m not free I know I am bounded in captivity

Bob Marley, (Concrete Jungle)

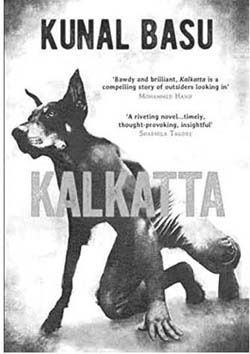

Set against the backdrop of the Partition, this novel narrates the story of Jamshed Alam, a Bihari Muslim boy born in the infamous Camp Geneva in Dhaka and raised in Kolkata, a city his poor refugee parents migrate to hoping for a legally secure, economically rewarding and socially dignified life. But does the city deliver what the Alam family seeks? The unfolding lives of Jamshed, his polio-stricken elder sister Miriam (Miri), tailor-father Abu, and seamstress-mother Ruksana in 14, Zakaria Street in northern-central Kolkata and beyond show how the city, much as they try not to fail it, eventually fails them. Cities and urban life is a theme that has fascinated (and disturbed) litterateurs across the world. It is the paradox of urban existence—with the promise of hope and freedom on the one hand and pathological alienation and melancholy on the other—that led, for instance, Balzac, Baudelaire and Modiano to reflect and write on Paris, Dickens on London, Joyce on Dublin, Isherwood on Berlin, Murakami on Tokyo, and Ellison and Auster on New York; needless to say, the list is endless. In India, three cities, namely, Mumbai, Kolkata, and Delhi, have featured prominently in both regional and non-regional literary writings. Kolkata, of course, is well-represented in early (19th century) as well as contemporary Bangla literature; Bhabanicharan Bandopadhyay (Kalikata Kamalalaya) and Shankar (Chowringhee) are but two of the many writers having done so. And then there are the English language writings on the city including, for example, Dominique Lapierre’s The City of Joy (original in French) and Amit Chaudhuri’s Calcutta: Two Years in the City; Kunal Basu’s Kalkatta, a noir(ish) fiction, is the latest addition to the list.

Kalkatta, as the name suggests, is about the non-Bengalis of the city. To be precise, it is a journey into the dark, dreary world inhabited by the Khottas and the Leres, pejoratives Bengalis often use respectively for Biharis and Muslims. Jamshed’s Kalkatta is far removed from the colonial grand legacy bearing, Anglophilic, high-cultured, Leftinclined, middle-class bhadralok Calcutta/ Kolkata about which so much has already been written. By choosing not to write about that sanitized Kolkata Basu makes an interesting literary and important political point. Indeed, the novel, by capturing the deep and dreadful anxieties which are part of the everyday existence of those who are culturally (and economically) peripheral, shows how Kolkata’s famed multi-cultural, pluralist ethos (the proof (sic) is: Kolkata has not produced anything like the Shiv Sena) is more a careful, calculated projection—a chimera— and less an organically evolved, authentic one. Interestingly, it is this exclusivist character of Kolkata that the anthropologist Nirmal Kumar Bose too discovers and discusses in his classic book Calcutta, 1964: A Social Survey. The refugee boy Jamshed’s encounter with the city begins after he, with the help of one Uncle Mushtak, a distant kin and local leader of the Communist party, gets a new birth certificate (and a new birthday— 25 October, the anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution) issued by the Indian authorities. Settled with his family in a run-down tenement, part of a larger Muslim ghetto, in the northern part of the city, Jamshed (Jami) starts school but, having fallen into disreputable company, eventually, much to the chagrin of his mother, quits it.

Continue reading this review