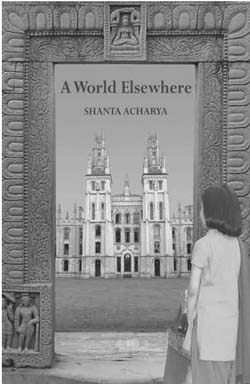

A World Elsewhere, a self-published novel by Shanta Acharya, is about a new world, a search for a state of being, a quest for meaning and for home—wherever that may be. Set in Orissa, India in the turmoil of the post-Independence years, in the clash of old and new world views, Anglophilia and Anglophobia, we are introduced to a hardworking, academic Hindu family who believes in the power of education, who struggles to maintain stability both within the family as well as in society, who understands that progress is needed for growth yet is bound by the demands of a closed society, especially when it comes to women.

Drawing on the elements of the historical and the picaresque novel, and strewn with quotes from several British and American writers, the author traces the childhood, loss of innocence and the many stages of awareness of the heroine, Asha, and to some extent explores her mother Karuna’s story as well. Acharya elaborates on the constant humiliation that women have to endure in a heavily gender-biased society, a world where no girl-child or woman is truly protected from oppression or some form of violence. Complex issues and several conflicting views are often presented in a ‘play of ideas’ series of discussions.

Very early in the book the reader is told that Asha is special, sensitive and bright, and as a child she is very religious and a dreamer, but given that when she grows up she has to marry and obey societal and familial rules, the plot becomes predictable. We fear that she will be bullied, be misunderstood and hurt. And so she is vulnerable as a child, as a teenager, and as a young woman who falls in love. Why does a brilliant, highly qualified young woman who could if she wanted, (against tremendous odds no doubt) decide not to take her future in her own hands? She thinks she is breaking the chains that bring her down but as we are sadly all too aware, she is dealing with forces far beyond her ken. Why does a scholar with a future in academia, jump into a relationship and then into a marriage that will nearly destroy her? Like the heroine of a romance, her neglected, lonely and naive heart takes over.

Unlike the heroines in Tagore’s The Broken Nest & The Home And the World, Asha’s character seems static even though her mind is constantly in turmoil, but at the same time like them is caught in the net of a male-dominated world. We cringe when we see what has become of the Guru family by the end of the novel, we celebrate that Asha makes a choice to move on after the traumatic end of her ‘love marriage’ but ironically, even her brother’s arranged marriage falls apart around the same time. Still the question remains— has she indeed ‘found herself ’? When she asks her mother, ‘Life has to mean more than this?’ Karuna’s resigned answer is, ‘… an illusion. Life is maya….’ To which Asha sagely replies, ‘We must learn not to stand in the path of our own happiness.’ But we are not completely convinced. Will the patterns repeat themselves?

Asha is now faced with the fear of Oxford and the racism inherent there, and what she is told by her contact in Calcutta, ‘Let’s hope you meet a few good men and women in Oxford’, echoes in her head. What seems more chilling is the brutal physical examination that she endures at the hands of the British doctor as part of the visa application process. A foreshadowing of what is to come?