Ulrich Beck in his much-acclaimed book Risk Society: Toward a New Modernity throws light on the consequences of a wide range of hazardous and deadly risks of a highly industrialized and urbanized society. He further elaborates that modern risks are not restricted to place or time, rather these risks are ever compounding and are multiplying exponentially thereby putting the entire world on high alert. Not surprising then that the new generation represented by Greta Thunberg dares to reprimand the world leaders for being unabashedly lackadaisical in their approach to tackle environmental risks. This insincerity on the part of the respective governments of nations across the globe towards ill management of environmental risks is something that has forced young children to intervene in ringing the alarm loud and clear. Ankur Bisen’s book Wasted: The Messy Story of Sanitation in India, A Manifesto for Change, packed with information (sans tables and charts) makes it readable for all concerned global citizens.

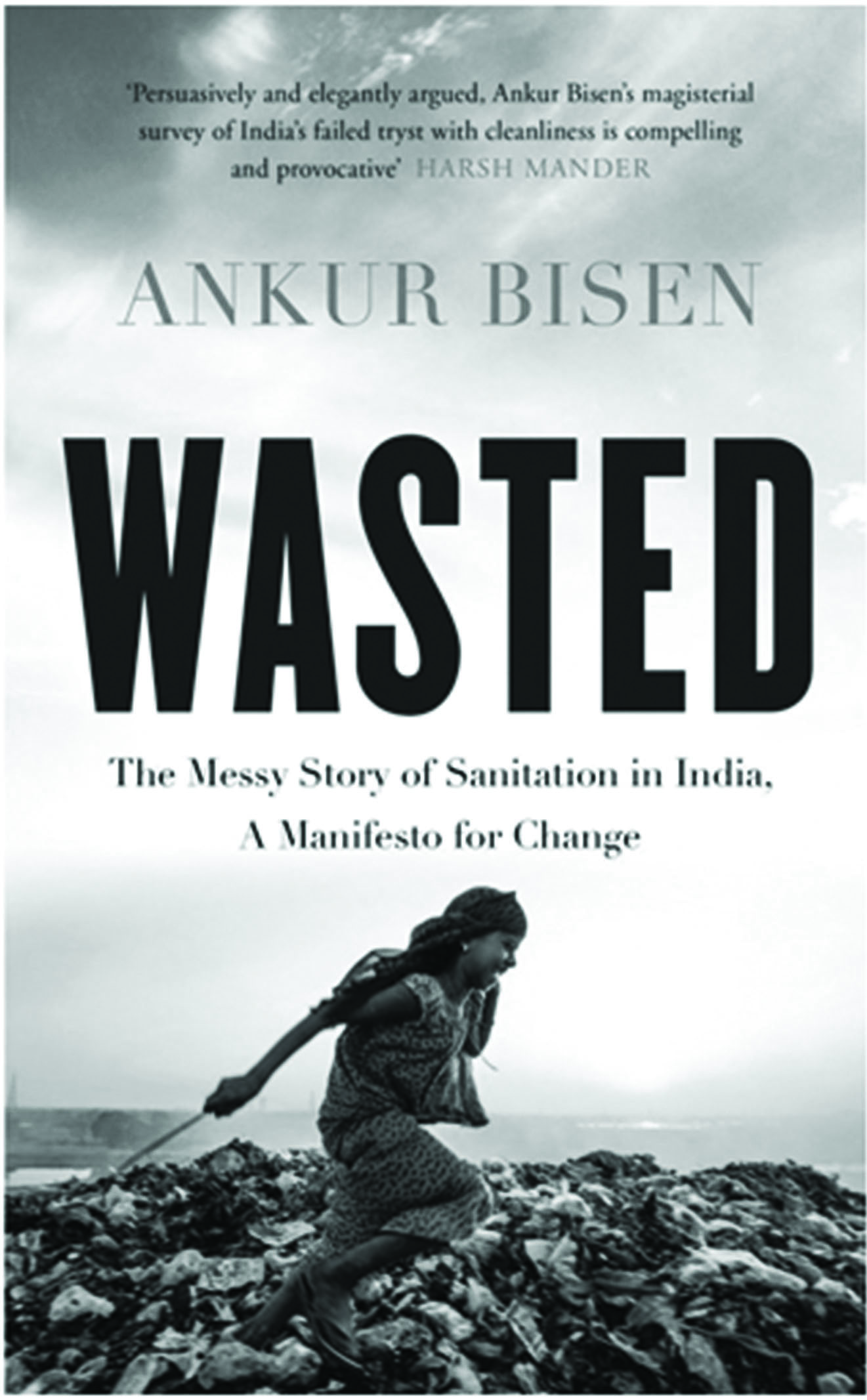

The cover illustration of Wasted is as captivating as is the book itself. The picture of a child rag-picker on a mound of urban garbage hopping in a wanton mood, unmindful of the risk it involves, and how the garbage dumps become the treasure-troves of the doubly underprivileged, speaks volumes about ‘the messy story of sanitation in India’.

Continue reading this review

The book under review problematizes waste management in India in a manner where the author tries to disentangle the intertwining of caste, sanitation, attitude towards hygiene and the deep-rooted apathy towards filth. Despite the entire landscape of India being dotted with untended mounds of garbage, overflowing open sewers, men urinating shamelessly in public places, open defecation being enjoyed as a group event, and poor children sieving garbage mound for sustenance, neither the state in particular nor the citizens in general show any concern about the havoc that such ‘Waste’ creates for the entire society. Why are Indians so stubbornly undisciplined in keeping their surroundings clean? Why is it that Indians keep their homes relatively clean while on the other hand they treat the public space as their rightfully owned dumping ground for all kinds of garbage? This book provides an insight into the psyche of Indian society at large as far as waste disposal and treatment of public space is concerned.

The author mentions at the outset that ‘there are no villains in this story, but there are biases and prejudices’ (p.10). The bibliography consists mostly of references from newspapers and journals. The absence of reference to books reveals the fact that for this pertinent issue not much has been documented or written. Wasted tries to fill this gap. Every library, private or public, should have this book on its stacks for the simple reason that it provides an intensive narrative about the creation of waste (it traces the history behind it), its disposal during the pre- and post-industrial times, and how with every technological advancement humans also create collateral hazardous waste. The author brings out the stark differences between the treatment of waste in India and in other developed countries by juxtaposing their respective sensibilities of hygiene.

The twin concepts of cleanliness/purity and pollution are anchored deeply in the socio-religious psyche of Indian society. The private space is treated as pure/clean while the public as impure/polluted. Furthermore, the problem gets compounded by the caste structure where cleaning of the public space becomes the duty of the untouchable caste. This practice has been there since antiquity, and will remain so unless Indians start owning responsibility for maintaining the public space in a similar manner as they maintain their respective homes.

Ankur Bisen tries to highlight the stark failure of the state in prioritizing sanitation and waste management despite being the world’s largest democracy. What is notable also is the fact that waste treatment was never accorded importance by the framers of the Indian Constitution. However, his remark that Indian need not suffer from inferiority complex just because the clean countries of today started their cleanliness drive a century ago is not well argued. On the contrary, the clean countries of today are clean because of the concerted efforts of both the state and the citizens to keep their respective countries clean.

One of the most informative chapters is the penultimate one that illuminates us on the hazards of e-waste, or the new generation waste. India is the third largest generator of e-waste, after the USA and China, and according to an estimate India annually ‘generates 2 metric tonnes of e-waste’ (p. 432). Unfortunately, any legislative effort to acknowledge the hazards of e-waste and thereby to make any effort to arrest its proliferation began only by 2015. India is far more backward than Japan in handling e-waste, or recycling it by using various processes such as metal extraction. The Indian political class is myopic in its vision that deliberately avoids taking stern measures to handle the hazards of e-waste.

What then is the panacea to make India a clean country? How far has the clarion call for ‘Swachcha Bharat’ been able to make an impact on Indian society at large? The author comes up with some viable suggestions in the last chapter, ‘Clean India: Capturing the Chimera’, to help India achieve comparable degrees of cleanliness with that of the first world countries.

Rafia Kazim