It is perhaps due to its ubiquity and our effortless access to popular visual culture in every day life that the ‘critical distance’ necessary to facilitate analysis of the field remains deficient. Popular culture in India characteristically presents itself in infinite, multiplying forms, percolating to the most private domestic spaces while also entering the city’s vast public areas as spectacles of celebration. The lacunae in research in this area in the subcontinent has been noticed by recent scholarship, and a spate of authored and edited volumes has surfaced to offer some insight. A significant contribution to the growing archive of studies on Indian popular visual culture is this latest volume by Marg Publications. Jyotindra Jain posits a key question in his Introduction to the volume, ‘What is popular culture?’ Often unreflectively seen as situated solely in mass production and mass consumption, it is usually linked to the common culture of the street (as against ‘classical’ or ‘traditional’ cultures), to the subaltern or working-class culture vis-à-vis that of the dominant groups’ (Introduction, p. 7).

The book unfolds to dwell on this idea as it explores undocumented subjects within popular visual culture while cautioning against too quick or too exclusive a definition of multiple practices that belong to the widest spectatorship socially possible.

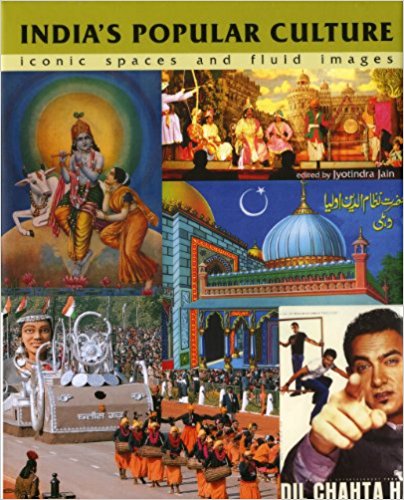

The title of the volume indicates a switching of conventional terms, for while iconicity is usually associated with imagery, fluidity can describe a spatial quality. The iconization of space then occurs where there is ‘the mythic and the real contestations of lived spaces’, i.e., the construction of spectacular ‘heterotopias’ as definied by Foucault.1 Exploring iconized space most literally in theatre is the essay by Anuradha Kapur, director of the National School of Drama, who deconstructs the visually opulent components (the curtain, backdrop, proscenium stage) of the travelling Surbhi Theatre Company in Andhra Pradesh. Surbhi has a unique visual vocabulary of stage sets that conjoin realistic perspective and fantastic colour schemes, narrating Indian mythology in the splendor capable of captivating remote audiences. More permanent, but equally utopic and fantastic constructions are the new high-rise residential flats in the outskirts of Delhi, analysed by social anthropologist Christiane Brosius. Here aspirations meet imagination in the global context and the national and international collapse to formu¬late lived spaces with ahistorical references. In location and function, the residential complexes remain conventional, yet in name, design, and claim to identity, they promise the lives of Egyptian pharaohs, modern-day maharajas and idyllic English villas. Advertise¬ments for such residential areas offer inter-mixed identities housed within gated, bubble worlds, detached and sanitized from chaotic, everyday India. Facilitating social hybridity are the cleat influences of external sensibilities on the Indian visual field, brought to the fore in the article by Savia Vegas. She cautions against the homogenized perception of Britain’s exclusive influence on Indian photography through the case of Goa’s Portugese colonial heritage and the distinct influence it had on family portrait photographs. In contrast, observing the government’s efforts at state sponsored national integration and cohesion, appears Jain’s own essay on the spectacle of India’s Republic Day parade where changing politico-social motives behind the celebration of stereotypes variously emphasize the Nehruvian ideal of unity in diversity.

The essays span a variety of visual media, making for a comprehensive study of popular culture. From theatre to advertising, and from photography to cartography, Indian visual culture has permeated sacred, celebratory, political and personal contexts-all of which have been presented here. Turning to the country’s engagement with the print medium since the nineteenth century, Ranjani Mazumdar, film theorist and associate professor at the School of Arts and Aesthetics, JNU, speaks of the accompaniments of India’s thriving film industry Lits film posters, their history and significance amidst town and city visual scapes. The print medium is discussed for its sacred worth by Christopher Pinney (Professor of Art History and Anthropology, UCLA) and Yousuf Saeed (independent filmmaker and researcher) in non-dominant, minority faiths in the subcontinent. Sacred posters of the Rajasthani dalit and adivasi deity of Ram Dev and the surprisingly populated posters of Islamic faith from the shrines of India and Pakistan are ethno¬graphically studied for their composition and meaning. These studies link the notion of space and its contestations with the variable of time by exploring the translation of sacred space into tangible, yet mobile material manifestations such as on circulating calen¬dars, posters, and postcards. Sumathy Ramaswamy’s essay on the cartographic realization of the nation and/on the globe through the mythological figure of Varaha upholding Prithvi provides insights into the negotiations between traditional faith and modern scientific discovery. Ramaswamy’s examinations extend beyond the visual productions of local mythology and structures, studying the rationalization in the Hindu belief system and the assumptions made by majority religions in propagating ideologies.

This volume successfully pushes the boundaries of any definition of the content of popular visual culture in terms of the hierarchy that it usually settles within, it melts the idea of a definite category of persons that produce/ disseminate/ consume its material, and it also opens the field to scholars from disciplines beyond art history. In the Indian context, visual culture does not exist independent of the heavy influences of art history, anthropology, design and film studies making it a porous area to be traversed by scholars from diverse backgrounds. This volume is a sourcebook for those interested in any of the above fields, and the results that emanate from their mutual interaction.

Suryanandini Sinha is working on her PhD programme at the Centre for Social Sciences, Calcutta.