Ever since the movies were invented, people have been writing about them. There was WG Faulkner, who, in 1912, became the first regular critic in a British newspaper (The London Evening News). ‘The picture theatre has taken a firm place in the social enjoyment of the people,’ he declared. ‘It is no longer a matter of wonder; it has become an everyday part of the national life.’ Americans like Otis Ferguson and James Agee followed. In France, young upstarts like Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut began to denounce the local produce, which they deemed largely inferior to Hollywood imports, especially if the films bore the names of Howard Hawks or Alfred Hitchcock. Then, again in America, Pauline Kael and Andrew Sarris (who brought to the US the term ‘auteur’) made criticism a duelling sport; so frequently at odds were they. A few decades later, the Internet exploded. Everyone started writing about the movies.

But almost all of those we know and revere as critics made their name from criticism. Agee was one of the rare exceptions—he was also a journalist, a poet. In other words, he was a writer first, a critic later (though, in all fairness, a critic is but a specialized kind of writer). Graham Greene was another writer who wrote about cinema—not for long, though. After viewing the child-star sensation Shirley Temple in John Ford’s Wee Willie Winkie, he sneered, ‘Her admirers—middle-aged men and clergymen—respond to her dubious coquetry, to the sight of her well-shaped and desirable little body, packed with enormous vitality, only because the safety curtain of the story and dialogue drops between their intelligence and their desires.’ The studio, unsurprisingly, sued for libel. After all, this was 1937, not the blogging era, where one can get away with anything.

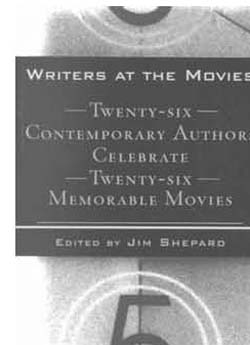

The contributors to the book under review are unlikely to have ruffled many feathers. Edited by Jim Shepard, it was published well into the Internet era, in 2000. The book is exactly what the title says it is. Twenty-six contemporary authors write about a film that affected them, that they found ‘memorable’. The most interesting aspect of the book, the USP, is that instead of consumers (critics, audiences) talking about films, we have creators of a different kind. After all, the likes of Julian Barnes, Salman Rushdie, Rick Moody and JM Coetzee have first-hand experience with narrative techniques, and when they look at films, they do so in fascinating ways.