Come, screaming with all your fourteen mouths,

You speechless hysteria hurting in each limb of my nation,

Come to me in the loneliness of your rage

Come out foaming

You the ‘Satvik’ blood of the centuries, I, a small poet

Stand hankering for your language,

Include me in your speech …. .

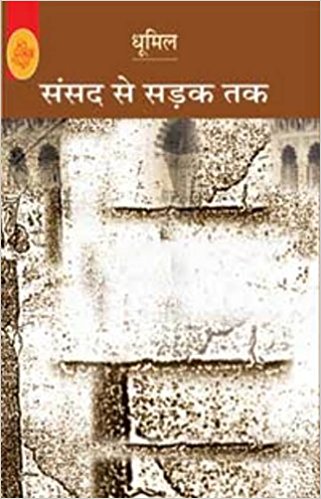

With the untimely death of Dhoomil in February 1975, modern Hindi literature lost one of its most promising young poets. In spite of his relatively small output, (his only published work is a collection of some 25 poems Sansad se Sadak Tak after which he published a few more poems in various Hindi magazines). Dhoomil had managed to attract attention with his clear and refreshingly new imagery and his adroit use of the Hindi language as it is spoken on the streets.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column] Dhoomil’s poems form a good basis for examining a new offshoot of modern Hindi poetry of protest and political involvement. Here for the first time, a conscious effort is being made to establish poetry-writing as a responsible act. In contrast to the lachrymose and subjective poems of the early post-Independence era, these are blood and gut poems which make no apologies of any kind: Time runs short, let us now start discussing our poems so the cities will lean closer to hear us ……. . The belief that poetry is eventually the most forceful symbol of mankind’s total powers of struggle against evil, runs through the entire poetry of Dhoomil. Poetry to him is not necessarily anti-politics but it is an autonomous act that stands on the same level and thus is competent to comment upon and analyse it freely. The central character of his poems is the ordinary Indian citizen, the man on the streets, who speaks to us of his profession, his social relationships and ties, using the ordinary images and symbols from his surroundings to point at a deeper truth that sublimates him into some sort of an ‘Everyman’, from old Christian plays. His world is rather crude and bare perhaps but it is far removed from the silly manners and mannerisms of the Indian upper middle classes: I only know That where the words are active The Hungers in a Mob Grabbed the lands of their brothers & whistled Dhoomil’s poems show a sensitive mind that matured in the post-Independence years and is trying hard to understand and analyse the socio-political forces at work around him. It starts as a search of, and a reaction against his environment: Is Independence then, a mere trilogy of tired colours? That a wheel drags along somehow, Or do they have a special meaning? Bees Sal Bad Soon the disillusionment comes in and also the anger– A total silence all round .. . the country, soaking in its hatred, holds me a prisoner today, as always. Pat Katha The above poem perhaps best illustrates the undulations of the poet’s psyche that moves from a forceful bitterness that lends his words a shining edge and incisiveness. Perhaps it was quite predictable that the poet should then turn to a more violent and destructive form of political thought. His much discussed poem Kavita Shrikakulam (Aveg November 1971) takes up the issue of the central forces of democracy giving way to violence of the sort that the Naxalites preached. But this seemingly inevitable outcome cannot last long either: Cowardice throws the empty gun and runs away and the grey-haired Prudence disappears in the dark. But while the suffering and the realization of the current discrepancies and problems is very stark and vivid in these poems, Dhoomil fails to provide any concrete visions of the world or the society as it will emerge after the confusing turmoil subsides: revolution for these misfits still remains, a pacifier in an innocent child’s fist. Akaldarshan Such a conclusion renders change both impossible and senseless. Perhaps if he had lived longer, Dhoomil might have arrived at a more solid and positive vision of human life and destiny. But even these stark and gloomy poems have a clarity of language and a raw and spontaneous energy that lends them a peculiar vital force. By far superior to these is the long poem Mochiram where the beauty and the sensuousness of the language and imagery carries the theme effortlessly forward. Here Dhoomil uses a way-side cobbler’s monologue as a very subtle and humane commentary upon the discrepancies and injustices inherent in the society that he inhabits: Each man is a pair of shoes to me standing before me for repairs … The images are mostly derived from the cobbler’s trade and the crowds that pass before him each day. There the thin man with shoes like bags of patches, who hesitantly puts his foot forward and smiles a smile, that flutters like a torn kite stuck on the telegraph wires, then there is the stingy braggart with a wrist watch on his hand who is not going anywhere but is always in a hurry. Apart from these there are beautiful images— The Spring ….. stretches the day taut like cat-gut strings hangs the insole—like red leaves upon the trees to dry in the sun and be seasoned slowly, At that hour it gets hard To hold the chisel straight, The hands this way, the eye goes that …. The poems ends on a note of acceptance : There are some who have acquired the words There are those who are blind to them, Who suffer each injustice in silence Scared of the fires within their bellies. But I know that the scream of protest And the discreet silence both are the same, They both create the future, just as they are. But sometimes Dhoomil, with the brilliant phrase or a striking pun makes his descriptions of the peripheral world seem like a sensational newspaper report- I saw with great wonder World’s greatest Buddhist monastery is also the biggest arsenal, the detached and leprous Gods that recline on the dirty margins of newspapers are called peaceful coexistence …. It makes one suspect that the poet is more keen to talk about life than create it anew in his poems. But perhaps it is representative of most current Indian writing where the writers and poets avoid an imaginative arrangement of their work but pick up the political slogans and idioms without altering the language. One feels that Dhoomil is inviting us for a revelation which eventually turns out to be a glimpse of the Indian life on the streets. But perhaps Dhoomil never strived for the poetic ambiguity of language that encompasses both conscious and the subconscious worlds. He wanted to be understood by the crowds in the crowded streets and was somewhat reluctant to take up the formulae for writing the kind of poetry that is considered eternal. With the language of the common man, Dhoomil also accepted the common Indian attitudes towards sex and women. There are very few references in his poems to recognized everyday relationships. Most of these, when they do occur, depict lassitude and sorrow— My mother’s face is a bag of wrinkles now … My wife’s tired pale face reflects me casually like a habit … The acceptance of the peasant’s world and language also leads him to accept his old primitive belief in the inferiority of woman. His women are passive and primitive beings surrounded with menstruations, pregnancies and abortions, singings songs of childbirth and fertility; ignorant and dumb. But he spares us the deliberate demeaning and abusing of women that is so disgustingly recurrent in the works of many other young Hindi poets. Dhoomil portrays the average Indian’s reaction to women subtly: Burning with his half desires, He is a would-be hell. Careful of himself, Whenever he sees women Dogs growl out of his pupils. Dhoomil had the frankness to admit his own ignorance and autocratic attitudes without any attempt at camouflaging them with a romantic imagery or a florid language: I am crude in my language and cowardly enough to be another Uttar Pradesh. In essence Dhoomil remains one of the few modern Hindi writers who made a conscious effort to break away from the smug and self-pitying attitudes of the literate middle classes and brought back to poetry an awareness of the class struggle that the common man in India faces everyday and in which language further acts as a subtly divisive force. Dhoomil’s emphasis on the need for a clean and expressive idiom in Hindi with which the masses can force their way out of this darkness of self-debasement and their pain thus has a double aim. It promises an expressiveness to the common man that he lacked, and further frees him from the English-dominated colonialism that the upper classes in the Indian society exercise upon him. He thus democratizes the whole concept of language and makes it a liberating force for people, who have said yes, yes too many times in other hands/limp and soft as wet clay. This is the future, meaning thereby a permission to enter the world of words, Now for the first time you Can make vocal your protest Against all the sorrows of years gone by. Praudh Shiksha (Translations by reviewer) Mrinal Pande is a well known Hindi short story writer. Review Details