‘I was my mother’s boy.’ ‘Amma took this shy, introverted child by hand and pushed him out into the world.’

‘I was forty-six the year Amma died. Even today, I inhabit the world she created in those forty-six years with me.’

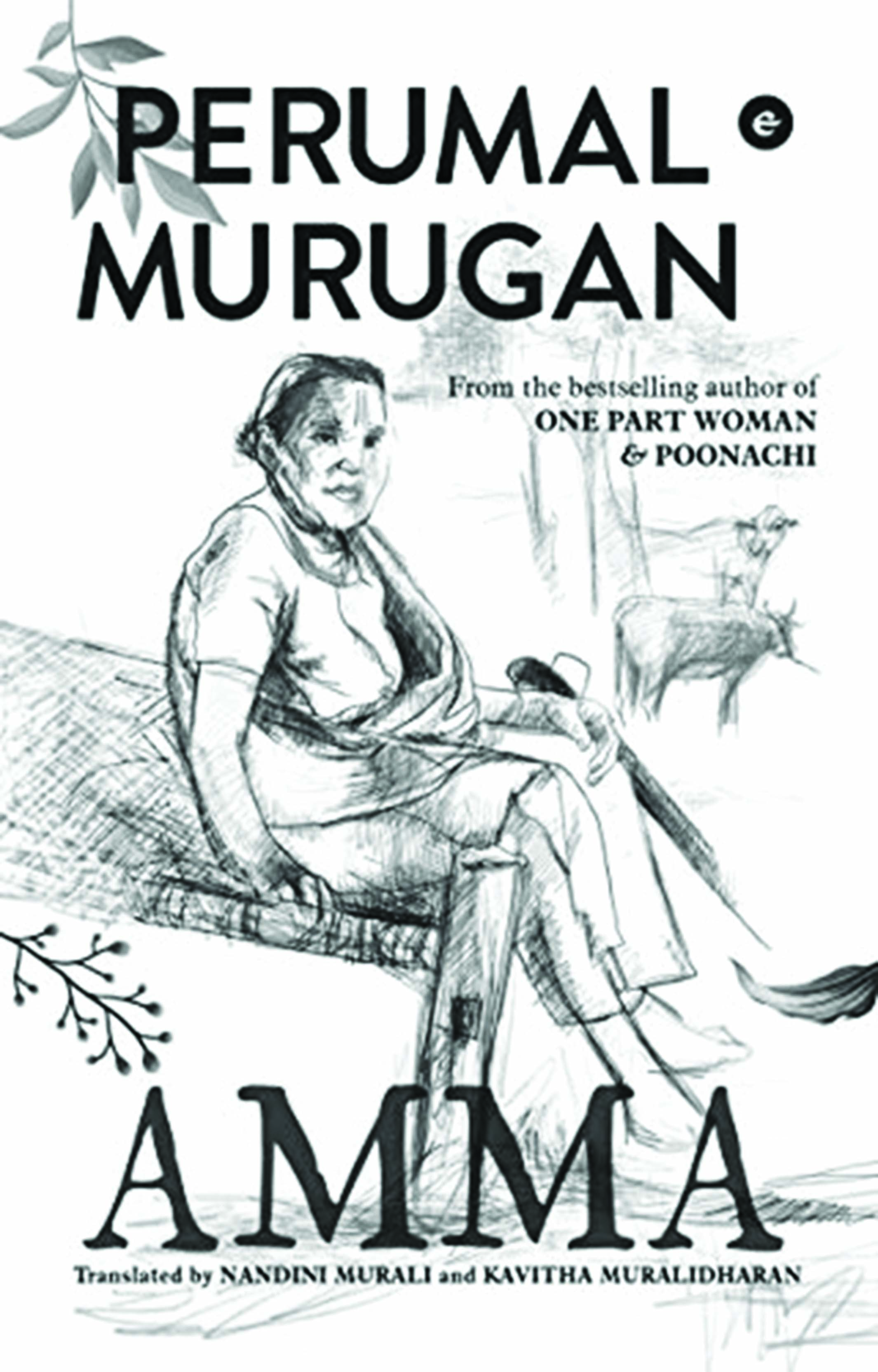

Amma, Perumal Murugan’s compelling memoir of his mother, is sprinkled with such tender declarations of affection and yet, the book is not a saccharine trip down memory lane, which, in fact, is its triumph. ‘There is no need to elevate this as some special kind of love. We fought often, and tantrums were common enough,’ the writer cautions right at the outset, flattening the usual expectations around such a narrative. What emerges instead is a robust rendering of a way of life steered by simplicity, hard work, contentment, and resilience.

In an outstanding translation that recreates the characteristic easy and uncluttered prose of Perumal Murugan, the duo Nandini Murali and Kavitha Muralidharan have made it possible for more readers around the world to be touched by this little gem of a book. The translators have tackled the thorny dilemma of whether or not to append a glossary by building it into the text, sometimes openly as in ‘thookuposis, round metal containers with handles’, sometimes unobtrusively as in ‘heavenly amudham’ or ‘she made kadaisal with mashed vegetables and lentils’—a technique that allows for the infusion of regional flavour into the text without unsettling the reader. The rendering of a term like Allah koyil as ‘Allah-temple’ instead of ‘the mosque’, which is what most translators would have done, is just one of the many instances of the translators’ remarkable sensitivity to the socio-cultural contexts of the text.

The book, notably, carries a foreword by Ezhilarasi, Perumal Murugan’s wife, who, in a few deft strokes, evokes a striking picture of her ‘athai-amma’. ‘Not your average mother-in-law,’ she says, but a comforting presence—firm yet caring, never one to evade work and unhampered by constricting beliefs. It took a long time for Perumal Murugan’s mother to reconcile herself to his inter-caste marriage and yet, what Ezhilarasi remembers distinctly is a great sense of liberation she felt ever since she moved into her in-laws’ house which more than vouches for her athai amma’s generosity of spirit.