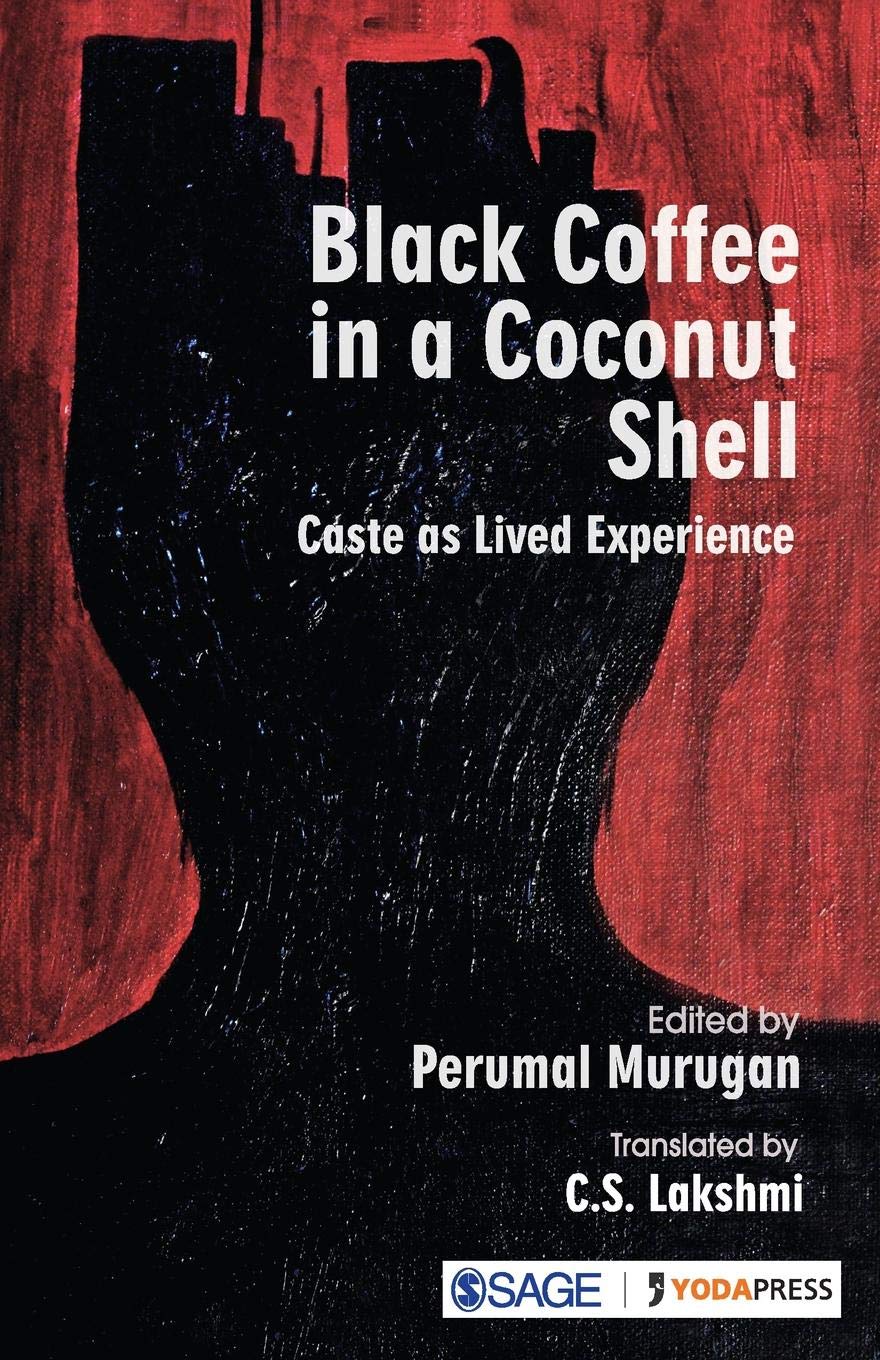

The articulations of caste and its deployment in India are grey areas that have been swept under the carpet and often rendered invisible in our quotidian lives. Many believe that it is a thing of the past that need not be talked about so vehemently today. But the agony of its experiential terrains, as recorded and performed by the millions who continue to be oppressed by its multipronged techniques of naming and shaming, both covert and overt, is profoundly revelatory. Such lived registers help one in looking at the social enactments of caste as they manifest and erupt all around us, questioning our liberal, progressive, secular and democratic pretentions. Black Coffee in a Coconut Shell: Caste as Lived Experience brings alive the pervasive toxicity of caste in everyday life as thirty-two voices bear testimony to how it made and unmade them, wreaking havoc in their lives. From birth to death, its cancerous tentacles enwrap all aspects of their lives from food, clothing, games, and gait to even the most private terrains of love and intimacy.

This book is lived history from below. As CS Lakshmi points out in her ‘Translator’s Preface’, what many in post-Independence India thought was that by merely asserting a casteless status and denying its existence staunchly, caste could be wished away, which it could not be because it marks bodies in a manner which needs confronting and overcoming. This seems precisely the function of this book, the single-minded purpose behind this meticulous translation of eclectic voices who lived and loved, knowing that their bodies and minds have been indelibly singed and branded by caste, that they carry this mark to their graves, in all their performances, rituals and social choreographies. However, as the translator rightly points out, these are not just sad stories. They begin with pain but often end in wisdom, self-reflexive, meditative and profound in their understanding of just existing with caste, of having gone to school with it, having been betrayed and humiliated in love by it, of having been served black coffee in a coconut shell, not for the lack of either milk or regular utensils.

The ‘Introduction’ by Perumal Murugan speaks poignantly about the difficulties faced by many in writing about caste. The stylistic and tonal variations in the personal narratives on caste make some writings in the form of complaints, while others are singed and seared by guilt, while for yet others it was in a confessional mode that made them feel lighter after the exercise, while for many it offers the scope of testimonial writing, of having borne witness to historical atrocities. The volume offers hope in that none of the writings support caste domination in any form, and therefore become harbingers of a new dawn, however Utopian it might sound today.