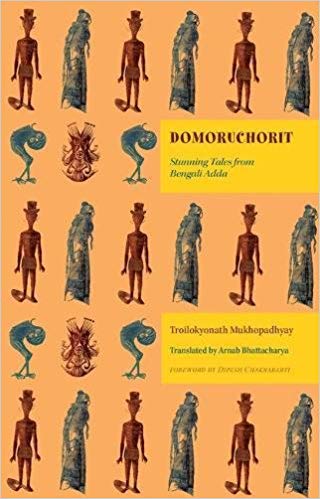

Domoruchorit by Troilokyonath Mukhopadhyay is a collection of seven stories describing the incredible adventures of Domorudhor, located in the outskirts of Kolkata at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Dipesh Chakrabarty’s introduction discusses the folkloric tradition that is discernible in the text, and places it in the tradition of novels in which the protagonists narrate tall, exaggerated tales about themselves. Chronicled by this focalized narrator, a sort of anti-hero, through the leisurely mode of the adda, it is a series of facetious and irreverent interactions between Domorudhor and his friends Lombodor and Shonkor Ghosh. In the course of the raconteur’s merging of factual storytelling and reminiscing with the spinning of bizarre anecdotes, the interface between the real and the supernatural is sometimes blurred, but at times challenged by his listeners.

I was mystified by the language of the translated text, its deployment of numerous words that sound outlandish, obscure, almost manufactured, like pong, bop, gobsmack, clomp, shemozzle, gofer, lekgotla, screed, jeremiad, hunker, scunge, razzle (the list could go on). I discovered that they are all valid words, often permitted within informal or comic usage in English. I also checked that both the original word and corresponding dictionary equivalent in English are both pretty standard ones. Lekgotla is jatala (meeting) in the Bangla text, shemozzle is gole (noise) and razzle is naach (dance). But the use of a vocabulary in English that is onomatopoeic and often visually imaginable gives the translation its earthy, rustic, folksy flavour in a way that a mere formal translation would not be able to.

Similarly, the unfamiliar idiomatic expressions scattered through the text sometimes had me bemused. Although I could deduce their general meaning, I ascertained that each one of them is a legitimate proverb in English. I have taught English literature for forty years now, but I had not known of many of them. ‘Seeing me in the buff’ (seeing naked), ‘rat me out’ (expose) or ‘knocking the old bat into the middle of next week’ (beating severely) are certainly more colourful than their cut-and-dry, verbatim English counterparts. The Bangla text mostly describes these phrases literally—for ‘rat me out to Durlobhi’, the Bangla text merely says Durlobhi ke giya khobor diyachhilo (went and informed Durlobhi), for ‘you have already talked a blue streak’ it has anek to shunilam tomar kotha (heard enough of your chatter), for ‘ran hell for leather’ the Bangla text has douriya…hnaap chharilam (fled and heaved a sigh of relief), for ‘boarded the gravy train’ it says du poishasongotiachhe (I have adequate means) and for ‘living in clover’ it says shukhenirapode bash koritechhi (living happily and safely). But the Bangla text is culturally rooted, so it does not need appealing to the senses to be graphically evocative to its readers. The only idiom I could not trace was ‘penny pincher of the first water’ (p.101) but I assume that was an erroneous replacement for ‘penny pincher of the first order’. The idiom ‘sating hunger with lime’ (p. 27) used to describe marrying for the third time, metaphorically represented in Bangla as pittirokkhe (causing bile), is also untraceable in English.