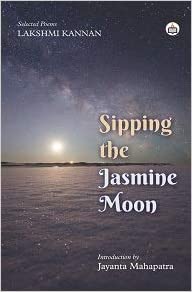

Poet, novelist, short story writer and translator Lakshmi Kannan is bilingual, writing fiction in Tamil in the name of ‘Kaaveri’. Sipping the Jasmine Moon is her fifth book of poetry. Rivers, river myths, family relationships, friendship and spirituality are important topics, but the over-arching concern is with woman’s fate in India. Of the sixty-six poems here, thirty-eight are new.

The poems are in five thematic sections. The first section, ‘Braided Lives’, with twenty poems, is centred on women. ‘Don’t Wash’ is a tribute to Rassasundari Debi (1809-1899) who taught herself writing by scribbling secretly on the mud walls of her kitchen. The poem ‘Family Tree’ reveals how a woman’s work is never recognized. Many poems are about the iniquitous property laws. ‘Red Ants, Then As Now’ is a beautiful recreation of the poet’s happy childhood in her grandfather’s house in Mysore, ‘A luminous beauty in cream colour/ with walls warmed by love.’

Thanks for sharing your thoughts on holiday.

Regards

my site :: https://casinoselection.populiser.com/

Thank you for every other wonderful article. Where else mayy anybody get

that kind of info in such a perfect manner of writing?

I have a presentation subsequent week, and I am on the search for such info.

my web-site; http://www.thegarrison.eu/forum/member.php?u=74719

Definitely believe that which you stated. Your

favorite reason seemed to be on the web the easiest thing to be awarfe of.

I say to you, I certainly get iked while people consider worries that they

just don’t knpw about. You managed to hit the nail uplon the top aand defined

oout the whole thinhg without having side-effects , people can take a signal.

Will probably be back to get more. Thanks

Take a lpok at my web blog Forums.panzergrenadiers.Com