Since the l960s, children’s books in the West have tended to ‘critically address tendencies to assume that the world is white, male and middle class’ (John Stephens). Those children’s stories in Bangla that reproduce real life situations, too, have been peopled by the middle class, espoused its values and focalized on the ubiquitously urban and urbane male child protagonist. When there are persons outside this comfortable, complacent, respectable, male universe, the characters are either criminals, or underprivileged children in need of patronage or charity. Sometimes, they are interesting servants, street acquaintances, magicians and jugglers living in the peripheries who lure the children into exciting alternate ways of life. The endings of the stories, however, confirm that these outlets are not viable in the long run.

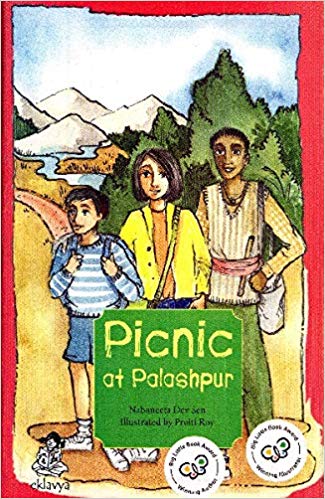

But Nabaneeta Dev Sen’s story is refreshingly different. Sen is a well-known children’s writer, apart from being a reputed academic and writer for adults too. This long short story by her is beautifully designed and illustrated by Proiti Roy, and an Eklavya publication that is easy on the pocket. It begins typically with two children on a holiday with their parents who go off on a picnic, described by the blurb to be an ‘adventurous trip’. But it is not the kind of adventure one would expect—getting lost, kidnapped or encountering criminals that would entail the solving of a mystery. The children here do not face any threat to their safety that is happily removed to get them back on the rails of their cushioned lives. In fact, they do meet a criminal, but he becomes an object of their curiosity, compassion, and eventually camaraderie. Initially, he is a sad, blind but somewhat scary figure who claims he lives like an outcast in the unpeopled hill they climb, crossing the threshold of their secure holiday retreat. He eats the flesh of small lizards and birds to survive. Thereafter, he confides in them that he was a Naxalite who got caught robbing a bank in a step towards removing the gap between the rich and the poor. Later, he was blinded by police brutality and managed to escape from prison. Although he has ever since realized that terrorism cannot cure any social evil and has leaned towards being a Gandhian, to the children he is still an ostracized man who was punished for his anti-social act. Yet they not only give their food to him, but empathize with him and promise to come back and visit him. The escapade certainly provides a space for them to rethink their middle class morality, cautioning them to keep such criminals at arm’s length. Sen’s story leaves room for negotiating a feasible relationship between these characters from radically disparate backgrounds.