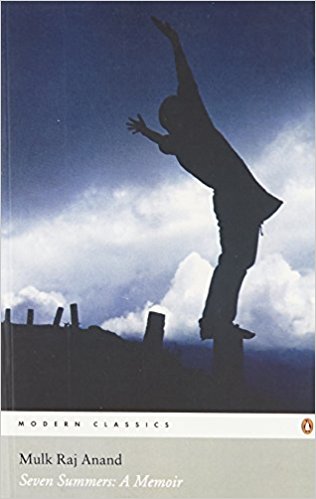

In a sultry evening in Delhi, here I am, reread-ing Mulk Raj Anand—from time to time kicking in the air to ward off aedes aegypti. For most of us Indians, the history of reading is in two parts. If you are not educated in a public school, you have to wait until you have learnt enough English to begin reading books in English, while you read—or you are read to—in your mother tongue at a very early age. This was the case in point for me. At a time when there were very few public schools, children of my generation from rural India spoke, read and dreamt in our mother tongues. That is why Mulk Raj Anand could enter my history of reading only belatedly – when I had picked up enough knowledge of the language he wrote in. Under review are two books by Mulk Raj Anand, Seven Summers: A Memoir and Selected Short Stories. If the memoir was first published in 1951, some stories included in the collection date back to 1930s. Both are reprinted now to mark the birth centenary of the departed writer. The fact that these works were written half a century ago may alarm the readers. For, for the present-day readers whose literary sensibilities have drastically changed during this period, fifty years seem to be a long period, long enough to render even a good fictional work a mere antiquity.

December 2006, volume 30, No 12